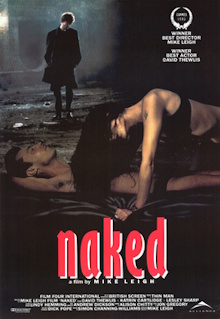

Mike Leigh is a celebrated auteur of British cinema so it’s unfortunate that the only film of his that I’ve watched to date has been the mediocre Peterloo. To remedy that, here is one of his best, a film whose dialogue is so dense with British colloquialisms that it’s difficult for us to parse. The main character here reminds me a great deal of the one in Henry Fool, cynical losers who are intelligently and weirdly attractive to women. But this film goes to far darker places with a cast full of equally broken people. It is funny in parts but there is nothing amusing about it at all.

While having sex in public in Manchester, Johnny gets violent and the woman threatens revenge. He steals a car and flees to London, arriving at a house where a former girlfriend Louise stays. She is unenthusiastic about seeing him but her housemate Sophie is fascinated by his philosophical ramblings and cynical views of life. After he has sex with her, she declares herself to be in love with him but then he seemingly loses interest and wanders off. Walking around the streets, he runs into a man and a woman who are looking for each other, then sits outside a posh building to read the books he is carrying around in his duffel bag. Brian, the security guard inside, notices him and being a reader himself, lets him in to get out of the cold. They have a deep conversation together about Johnny’s ideas about the impending apocalypse and despite his critique about the pointlessness of Brian’s job, they seem to enjoy each other’s company. Brian points out a woman who he watches sometimes at her window in the building opposite and so Johnny goes over to introduce himself.

Just like Henry Fool, I disliked this film at first because it similarly features a loquacious grifter who wields his learning as a weapon yet is charming to some women. The dialogue here is far better and even though I can’t claim to be able to understand all of his jokes, some of his puns had me laughing out loud. He is self-aware enough to adjust the sophistication of his humor or mockery to the level of his interlocutor, never seems to run out of cigarettes and his sheer brazenness in asking for things lets him get by despite being penniless. The difference is that Leigh does not endow him with a heart of gold. He is a cruel bully and a misogynist who is driven to hurt women while having sex with them. You might feel sorry for him and others like him on the fringes of society, but you are not meant to like him. Interestingly, the film also introduces a character who is in some ways his opposite: the rich, psychopathic and sadistic Jeremy who is apparently the owner of the house. He inserts himself into the house doing whatever he wants and Louise and Sophie are so scared of him that they choose to leave rather than make a fuss. I interpret this as being Leigh’s indictment of the kind of person who thrives in the UK under the government of that era.

The richly layered dialogue and complex characterization wasn’t the work of Leigh alone. Instead he briefed the cast on the characters he wanted them to play, assigned readings to David Thewlis who plays Johnny, and had them interact in character to develop the script through improvisation. It’s no wonder that Thewlis shot to fame after this. I especially appreciate how the film shows that broken people like Sophie fall hard for Johnny. But those who are more put together like the waitress from the diner are strong enough to reject him even though she is lonely herself. There is no happy ending for him and his charm doesn’t mean that he gets to escape the consequences of his lifestyle. Johnny continually disparages the people who settle for ordinary lives, working jobs, making money and settling for mediocrity as he sees it. Yet it’s important to note that the film itself doesn’t do that. It ends on an ambiguous note but I have no doubt that unless there is some drastic change, Johnny is doomed to die alone on the streets.

We never learn exactly what happened to Johnny that made him this way or the nature of his relationship with Louise. It’s better that the audience is left to imagine these details for ourselves so that we can relate to him more. I’d consider this film a true masterpiece and a much better example of what Leigh achieved at the height of his career. In the end, this isn’t much like Henry Fool at all which after all was a kind of fairy tale. This one is a tragedy through and through.