Back when I started my series of “Favorite Films” posts in 2007, I took extra pains to define what that title meant. It isn’t sufficient for a film to be merely entertaining and likeable. A film must pass that test, I thought, but more than that it must also aspire to be a work of art. Either by conveying a profound meaning or by expanding the vocabulary of cinema through innovation.

However I failed to consider that it might be possible for a film to fail the first test but completely blow the competition out of the water on the second. For this reason, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life is in a class of its own. I do not find it entertaining. Yes, it is utterly captivating to watch but it is also so intense that it is too mentally exhausting to be considered entertaining.

I do not find it likeable. Its central theme is very Christian. Indeed, the film threatens to be incomprehensible to anyone who does not know the Bible. I do not need to tell regular readers of this blog why I find this philosophy offensive, especially as the emphasis here is on acceptance and surrender. As for its setting, I understand that its images of life as a child in 1960s suburban America speaks volumes for certain audiences but it does nothing for me.

Yet if The Tree of Life doesn’t appear on my list of Favourite Films there is no good reason for such a list to exist. One aspect of this film stands out above all others: its soaring ambition. It attempts nothing less than to tell the story of all life on Earth through the lens of a single man’s childhood experiences.

To this end, it takes a page from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which fortunately my wife and I have only recently watched. The entire history of the Earth, in compressed form, is told through a series of images, beginning with the Christian account of creation, to the forming of the planet and to the development and evolution of life on Earth. As with 2001, many of these scenes were made using practical effects rather than CG, which gives them a vivid, organic look completely unlike anything else you will see in modern films.

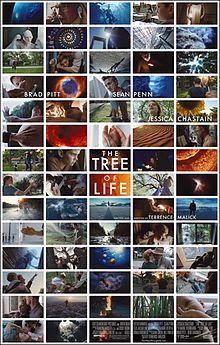

These images bookend the childhood of Jack O’Brien as raised by his father, played by Brad Pitt in his most unglamorous, regular bloke role yet, and his mother. The life is ordinary but the themes are rich and complex, encompassing such difficult subjects as Oedipal urges and a love-hate relationship with his father. Every image is composed and shot with an exacting eye to detail and the precision of a master craftsman. In one scene Pitt’s character comments on how Toscanini once recorded a piece 65 times and still claimed later that it could have been better. Malick might well have been referring to his own quest for perfection.

The end result is a superlative work that challenges what films can be. As Roger Ebert states in his review, most directors settle for making good films. Terrence Malick intends no less than to make masterpieces. In a now classic review of the videogame BioShock, Tom Chick tried to answer the question of whether or not videogames can be art by pointing out, “Games are this.”

In the same way, it is truly glorious to be able to point to The Tree of Life and say “films are this” as a demonstration of what a master filmmaker can accomplish when he really puts his mind to it.