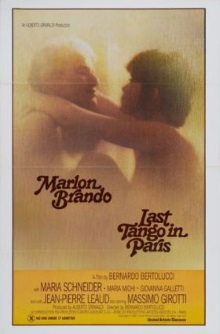

Last Tango in Paris is one of the many films that my wife watched ages ago but I am only now watching for the first time because, well, I only recently started to take films seriously. Fortunately for me, my wife confessed to not really understanding it when she last watched it, so in a way, we were still discovering it together.

There is absolutely no question that this is a film that needs to be watched by any aficionado. Roger Ebert included it in his list of 100 Great Movies and it is the subject of a review by Pauline Kael that is considered the most famous film review of all time. But after watching it, I found it to be an exceptionally difficult film to think about, let alone write about.

Let’s start with the things that are easy to agree with. Both Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider deliver exceptional performances. I find myself agreeing with Ebert about how only Brando could have combined such aggressive masculinity with such child-like fragility. It creatively uses music to upset the usual expectations in a very meta way. The cinematography is both immaculate with effective but unobtrusive camera work and deliberately contrasting colours.

Also indisputable is the sheer power of the emotions displayed. Its rawness is such that we are shocked out of the role as the audience and feel uneasy at being voyeurs to such intimate scenes. There are sex scenes and nudity aplenty in this film but none of it is for our titillation. Indeed, lust is not what drives the characters here. Brando’s Paul clearly uses Schneider’s Jeanne as a means to work out his grief and rage following the death of his wife. Jeanne, for her part, seems addicted to his charm and the strength of his need.

It makes for uncomfortable viewing because there is no audience surrogate to sympathize with. We see that Paul, who appears more than twice as old as Jeanne, is a sexual predator and sense that their relationship can only end badly. Our anxiety is further heightened by the stark juxtapositions. We are shown the arches, boulevards and Haussmanian architecture of Paris, which years of cinema have trained our minds to associate with romantic hand-holding and sweet kisses. So we startled by the vulgarity of the pair. “Stick your finger in my ass,” Paul instructs Jeanne as he braces himself against a wall. Similarly, the formal tango of the title is abruptly interrupted by Paul literally taking off his pants in public to moon the shocked dancers.

We also discern that this is a film with multiple layers of meaning that are open to interpretation. Jeanne’s fiancee, Thomas, sometimes feels like an extraneous character. This relationship seems weak and shallow, in fact very much a caricature of traditional movie romances. He even insists on capturing and idealizing this romance on film. Superficially, this of course serves to clarify why Jeanne is so attracted to the unfiltered rawness of Paul’s attentions, but it’s not hard to imagine a deeper statement about the very nature of romance behind it. Another example can be found in Paul’s monologue before the dead body of his wife, Rosa. We get a hint that perhaps he may have had an analogous relationship with Rosa, but with the roles reversed.

Yet however much one can admire this film, both its subject matter and the story behind its creation makes it hard to like. Both Brando and Schneider felt manipulated and used by the director Bernardo Bertolucci. It could well be that the film feels so powerful only because Brando is playing himself and Schneider’s fear and pain is all too real. It becomes even more disturbing when you learn that Bertolucci developed this out of his own sexual fantasies. This is I think a film that fully deserves its reputation both for its cinematic greatness and for its controversy, though perhaps not for the usual moralistic reasons.