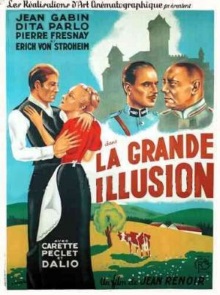

Continuing with our tour of the great classics of cinema is Jean Renoir’s La Grande Illusion. We’d previously watched his La Règle du Jeu which I found to be a complex and wickedly funny dissection of the European upper classes and their social structures. So I was really looking forward to this film that is set during the First World War.

Despite the setting, this is a war movie with no battles and barely any violence. Two French aviators, the aristocratic De Boeldieu and the working-class Maréchal, are shot down while on a reconnaissance flight over Germany and captured as prisoners-to-war. There they meet Von Rauffenstein, who despite being German, feels empathy with De Boeldieu for being a fellow aristocrat of the Old World. The film then follows the French prisoners as they interact with each other and are moved from camp to camp.

Unfortunately my own response to this widely lauded film is merely lukewarm. One reason for this is not at all the film’s fault, being that some its best scenes have had their thunder stolen by films that came later. Its depiction of digging a tunnel to escape from a prison and particularly how they dispose of the dirt in the garden, is practically a cliché of prison escape films. It also turns out that the stirring rendition of La Marseillaise to antagonize the Germans made famous by Casablanca came from here. As much as I appreciate that La Grande Illusion did them first, I still can’t stop myself from feeling that these are all things I’ve seen before.

The same generally holds true as well for the main themes of its story. On one level, it shows off the basic humanity of its characters regardless of nationality and ideology as an argument against war. The interesting part here is that it doesn’t try to grimly convince you of the horrors of war. Indeed, life as a prisoner-of-war looks like rather pleasant experience here. Instead, it attempts to show why war as a concept is so ludicrous when people share so much in common and can get along with each other just fine.

On another level, it also highlights the class divisions that still exists in Europe. De Boeldieu and Von Rauffenstein, both cosmopolitan aristocrats, appear to understand each other better than they do with the common people of their respective nations. A nice touch is how they interchangeably speak French or German with each other as the mood strikes, but switch to English when talking about things that aren’t meant for the peasants. Interactions with a rich fellow French prisoner of Jewish heritage further illustrates these differences while emphasizing throughout that their common humanity transcends these divisions.

All this is laudable and interesting but there’s always the sense of déjà vu there. There’s also the fact that these themes are much more straightforward and simple than the complex, multi-layered meanings in La Règle du Jeu. The part where they encounter Elsa the German widow and celebrate Christmas with her and her children even comes across as trite.

For me, I think this film is best appreciated within the context of its time. It was filmed in 1937 just as a Second World War was coming to be seen as being inevitable despite everything that everyone had learned the first time around. It was clearly a last ditch appeal for peace and the fact that both the French and German governments banned it speaks volumes on its importance. For modern audiences the passage of time inevitably means that its significance will not be felt as strongly.