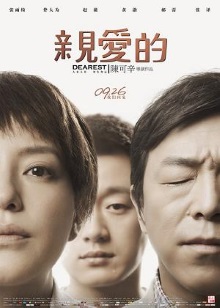

I currently seem to have a disproportionately large number of Chinese-language films sitting in my watch-list. Part of this is due to just making up for lost time but I like to think that it’s also due to China’s growing prominence in the international arena and its greater ability to score successes in the global culture wars. In any case I think Dearest is an example of a film that a is a near ideal confluence of being topical as it’s about modern China, being good enough that it deserves to be taken seriously and yet remains accessible enough to achieve commercial success.

This one casts light on the plight of child abductions in the country. Tian Wenjun, played by Huang Bo, one of China’s top actors, is a resident of Shenzen who has a son with ex-wife Lu Xiaojuan. One day while playing outside the boy is kidnapped, an event that tears apart the lives of the two parents even though Xiaojuan has since remarried. He goes to desperate lengths to find his son, trawling through the Internet to search for clues and travelling across China all to no avail. Years later however after they have joined a support group for parents of abducted children, an informant leads them to a small village. But by then the boy has lived for three years thinking that his mother is a local farmer Li Hongqin, played by Zhao Wei.

Made by veteran Hong Kong director Peter Chan, Dearest boasts impeccable production values, a strong cast, a powerful sense for human drama and perhaps most of all a subject matter that all but guarantees the sympathy of the audience. The testimony of the parents at the support group about how they cope with the loss is heartbreaking. The film captures both the pain and the moral ambiguity of forcibly reuniting children with birth parents after they’d been raised by adoptive ones who have come to genuinely love them. When the aggrieved parents mob Hongqin and beat her while she does nothing to resist, you know that it’s wrong but at the same time it’s hard to deny them this catharsis after all of the suffering that they’d had to endure.

Unfortunately Chan never knows when to let up and milks the drama for all that it’s worth. The spectacle of Wenjun and Xiaojuan snatching the boy back from Hongqin makes for a powerful statement when seemingly the entire village joins in the chase but gains a farcical quality when it drags on for too long. Similarly even after Hongqin has been convicted and punished, the film keeps piling tragedy after tragedy on top of her with a final twist of the knife at the end that is just superfluous. It’s such a blatant attempt to wring every last teardrop out of the audience’s eyes that the film loses the sheen of authenticity. We intuitively know that real life tends not to be so dramatic and so we’re reminded that it’s just a movie. Though the events here are loosely based on a true story, the real life events played out in a much more straightforward fashion as the child never even forgot about his birth parents. The movie version have to be perfectly faithful but does need to have a sense of restraint to make it believable.

Still, even if he goes overboard the director does get all of the details right so there’s no denying that it’s a good film. I appreciated the soft touch that he employs in showing how Wenjun and Xiaojuan gradually become closer again through their shared suffering while still remaining divorced. I liked how the camera doesn’t shy away from showing the urban poor, the flip side of China’s prosperous cities. The shot in which Xiaojuan opens the door into a dorm full of migrant construction workers from the countryside, the only woman amongst a crowd of men, is a powerful one. It all adds up to a solid film that can’t help but move you even if you are wise to its manipulations.

I do note that this film isn’t quite free from the hand of state censorship. Reading up on the topic, it seems that a major grievance of the parents at the time was that the government continually understated the extent of the abductions. One reason why the parents took so heavily to online platforms to help their search was that state media were reluctant to highlight the problem. The film is sadly silent on these issues. Yet at the same time, it’s brave enough to make some oblique criticisms including a clear jab at the injustices engendered by the infamous One Child Policy. Here’s to hoping that we’ll get more good films about the real China.