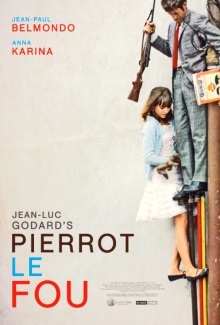

The last time we tried to watch a film by Jean-Luc Goddard, it didn’t go over so well. This one was made at the peak of the New Wave director’s career and even stars Jean-Paul Belmondo, who Goddard of course immortalized in Breathless. In the event, while this one at least had more of a plot that we could follow, it was still pretty tough to glean any sort of meaning out of it.

After losing his job, Ferdinand Griffon has been feeling directionless. He attends an inane party and becomes even more listless. He discovers that the babysitter, Marianne, his wife has arranged for the evening is actually an ex-girlfriend and decides seemingly on a whim to run away with her. After that the narrative gets a bit muddled. He finds a corpse in Marianne’s apartment and she seems to have plenty of guns as well. She weaves a story about her brother being a gun-runner but Ferdinand doesn’t believe her and so the audience doesn’t know what to think. They run away in the dead man’s car heading southwards to the Mediterranean Sea. They appear to have no money and so sustain their flight with a spree of crimes. Yet they somehow are able to settle down for a while to an idyllic life in the French Riviera where they fish for food while Ferdinand reads and writes in his diary.

As is par for the course for Goddard, the film is replete with cultural references of all kinds, which is one big reason why it is so hard to decipher. Even the running gag that Marianne always calls him ‘Pierrot’ while he responds that his name is ‘Ferdinand’ is a reference to a stock clown character used in French theater troupes in the 18th century. Other references are to films, including an overt one to Goddard’s own Breathless which shares some obvious thematic similarities with this own, literary works and even comic books. One way that Goddard is being “subversive” in this film is by mixing high and low culture: it opens with Belmondo’s voice narrating a deeply philosophical quote but when the camera cuts to his face, we see that he is reading the book while lying in a bathtub to his young child, undermining the weightiness of the moment. The deliberate use of loud primary colors is another example of this. At one point. Ferdinand even describes Marianne as the woman dressed in Technicolor clothes from an American movie.

Another theme in Pierrot le Fou is playing games with what’s “real” and what’s a construct of the narrative. As we watch the images of Marianne and Ferdinand on their adventures, they keep up a commentary of what they’re doing, except that this commentary is a work in progress that is constantly being changed and edited. This is another reason why watching this film is so confusing. You’re constantly asking yourself: is this really happening or are they just making it up? As the commentary changes, so does the apparent genre. Is this a crime film? A thriller involving spies and gangsters? A romantic musical? A Robinson Crusoe-esque escapade from society? It’s all of the above.

Unlike Adieu au Langage, Pierrot le Fou has impeccable production values and looks fantastic throughout. My wife commented that the film somehow manages to keep its energy level and its tempo going, so that even though you don’t quite know what’s going on, you feel compelled to watch nevertheless. Each of the set-pieces stand well on their own and I’m especially impressed by how earnestly Goddard made the musical scenes, complete with perfect choreography, great looking backdrops and enjoyable singing. Even if you miss out on the deeper themes, this means that the film might still be fairly entertaining.

Still, this isn’t anything that will move you and you’re unlikely to empathize with Ferdinand or his strange plight. It strikes me that Goddard is a filmmaker who aims to appeal to the mind instead of the heart. His films are so cerebral and so dense that they force you to do a lot of work to get anything out of it. It is certainly true that I grew more impressed by this film after thinking more about the film during the writing of this post.