This is a follow up to The Act of Killing, one of the most hard hitting documentaries I’ve ever seen. Director Joshua Oppenheimer is joined this time by a middle-aged Indonesian collaborator who appears onscreen but will not reveal his name for the safety of himself and his family. If you stay around to read the credits at the end of the film, you’ll also notice that plenty of other contributors including researchers and even cameramen have similarly chosen to be anonymous, an indication of how dangerous these revelations still are even decades after the massacres.

The main collaborator is a travelling optometrist who uses the opportunity of fitting glasses for the people he visits to talk to them about the events of 1965. From his interactions with his aged parents, we learn that he was born a few years after killings and that he has an elder brother named Ramli who was a victim of the purge. He also watches videos that Oppenheimer had previously shot showing the killers and their leaders openly boasting about what they had done. He visits both ordinary people who participated in the killings as well as leaders, including one who is now in that state legislature. He even discovers that his uncle, his mother’s brother, indirectly participated while working as a guard for the prisoners. None of the killers express remorse for their actions though some of their family members do. He also connects with a survivor who managed to escape from the death squads and there’s a particular emotional moment when his mother meets and recognizes this survivor.

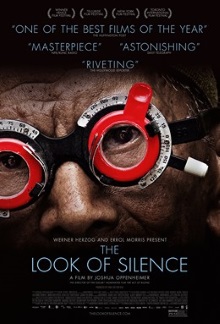

After the first film, that these mass murderers are walking about freely is now less shocking, but the additional testimonies here are no less chilling. The title is well chosen as the optometrist’s solemn face as he watches the videos of the killers boasting about their exploits, including anecdotes about them dealing with his brother is gory detail, speaks volumes. It also applies when he properly identifies himself. When he first asks his interlocutors to describe what they did, they are usually proud and happy to talk about it. One says that the U.S. government should reward them with a trip to their country as it was the U.S. who taught them to hate communists. But when he tells them that his brother was one of the victims, the mood of the conversation instantly changes. The interviewees clam up and make vague excuses about how it’s getting late. In the end, they are left uncomfortably staring at each other with nothing to say.

The film is fascinating to watch in a sort of sick way as an aperçu into human nature. The killers and their families, even the most well meaning ones, are always eager to say that the events happened so long ago and everyone’s memories are hazy, so it would be better to just forget about them. To them, talking about the painful subject would just be reopening old wounds. But it’s clear that to the victims and their families, the wounds never really healed. The families of the killers may only have a vague idea of what their family members did and have no knowledge of who they killed, but as the optometrist states, each and every family of someone who died know perfectly well who the killers are, who their descendants are, and where they live. They may have no hope of getting justice or vengeance and justifiably fear reprisals if they make a fuss over it, but that doesn’t stop them from praying in their hearts everyday that the killers and their family members die horrible deaths.

In between the interviews, The Look of Silence presents us with scenes of the optometrist’s family. These are often shockingly intimate, such as his two children joking and playing with each other. It’s a testament to how much time and effort Oppenheimer must have devoted to this project that they can be so completely at ease with the camera and so trusting of him. They remind us, without having to put it in words, of the strange incongruity between the thoroughly modern children, with their toys and shopping malls, and the fact that Indonesia has never fully come to terms with its awful past. There’s just something deeply disconcerting that this modernity and civilization coexists with people who openly state that they drank the blood of their victims to prevent themselves from being driven insane due to all the killings. At times, this intimacy does seem to go overboard. The shots of the optometrist’s father who must over a hundred years old and suffers terribly from dementia helps us sympathize with his family but feels voyeuristic and somewhat off topic.

Overall this is a fine companion piece to the first film and should be watched by just about everybody. Its lessons and insights are highly relevant especially given the tumultuous political events this year. For example, witness how the killers and those who enabled them quickly retreat to the statement that they refuse to talk about politics when pressed, as if everything wasn’t ultimately about politics. Many struggles are really about who holds power, and by extension wealth, and what they are willing to do to keep it. As this documentary shows, humans in general are willing to go pretty far indeed and frighteningly have no problems sleeping at night afterwards.