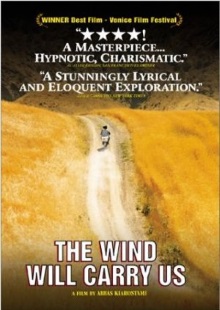

As astute readers might intuit, this was added to our watch on the occasion of the death of its director Abbas Kiarostami. I’ve previously covered one of his later works in this blog, but I’ve never watched any of the films that actually made his famous. Kiarostami was already a pretty big deal when he made The Wind Will Carry Us, but I believe this helped him cement his reputation at the height of his career, making it essential watching.

With a simple plot in which almost nothing happens, this film defies any normal attempt to summarize it. A group of men arrives at a remote Kurdish village by car following directions that they have been provided. A young boy shows the main character around the village and we gather that the villagers believe he is an engineer working on a project. The man however seems mostly interested in an old woman in the village who is on the verge of dying and asks after her everyday. Eventually it becomes obvious to the audience that he and his colleagues are actually waiting for her to die in order to record the mourning ritual. When he receives calls on his mobile phone, he needs to use his car to drive to higher ground to get good enough reception to hear what is being said. As the days pass, this becomes something of a ritual for the man. His colleagues and his distant boss become impatient as the old woman hangs on to life and tempers start to fray.

There’s not much in the way of plot but the film abounds with themes and symbolism. An obvious one is the shadow of death as they wait around. Whenever the protagonist drives to the top of the hill to talk on his phone, he chats with an unseen man who is digging a ditch there. On their very first meeting, he finds there a human femur which he casually plays with and places on the dashboard of his car like a trophy. There are hints that the man is ignoring a death in his own family in order this event. Then there’s how the man is cut off from the modern world with his phone being the only remaining link. The man is frequently condescending to the villagers, quoting passages of poetry to them, including one that contains the words of the film’s title, to which they have no answer. Yet, to me at least, there is a sense that these villagers live the kind of life described in the poems even if they don’t know them.

Not being a student of Iranian poetry, there’s only so much I can get from those themes. Even so, there’s plenty of mileage to be had from the beautiful images and the effortless pacing. The landscapes of Iran as captured here is simply breathtaking. The early scene in which the young boy takes the visitor on a tour of the village is delightful as they clamber up and down steps and walk across ladders to traverse the wonderfully three-dimensional village. Despite the repetitive nature of the man’s driving trips up the hill, there’s a strange, meditative power to the ritual. This goes double for the scene in which he enters the underground cellar in which the girl milks the cow.

As appreciative as I am of the qualities of this film, this is another of those cases in which the lack of a shared cultural context means that I find its message just ever so slightly out of my reach. It’s easy to see why so many people consider this a masterpiece but it would be unfair for me to give it such high praise when so much of it goes over my head. Still, there’s no doubt that this is a fine film and a wonderful depiction of a Kurdish village in Iran.