Crime spree films featuring a couple, usually a man and a woman, going off on a wild ride of robberies and killings until they die in a hail of bullets are common enough to constitute a genre in of themselves. Bonnie and Clyde is far from the first of these films but it’s easily the first one that comes to mind when you think about them, especially for American audiences. It’s also one of the earliest American films to show a very obvious French New Wave influence, sharing remarkable similarities in particular with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless.

Bonnie Parker is a young woman in rural Texas who is bored of her life. When she meets Clyde Barrows who appears to be trying to steal her mother’s car, she is fascinated by his claim of being a robber and falls in with him. Armed with Barrows’ pistol, they travel around robbing shops and stealing cars but their takings are desultory, partly because of their amateurish efforts and partly because it’s the middle of the Depression and most people are poor. Their crimes become more serious once they pick up C.W. Moss, a pump station attendant, as a member of their crew and Barrows kills a bank manager. Soon after Barrows’ brother, Buck, and his wife, Blanche, joins them, they become celebrities, with the newspapers attributing outlandish crimes to them that they were nowhere near. Despite the multi-state manhunt for them, they get lucky time and time again, racking up an ever growing body count. Parker even gets her poem that romanticizes their exploits published in the papers. Of course all such sprees come to a bloody end eventually and it has to be said that the obligatory hail of bullets here is even bloodier than I expected.

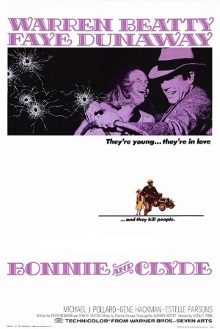

There’s no question that this film both deserves its glowing reputation and is entertaining to watch. The interactions between Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway are engrossing from the get-go as she goads and pushes him to be more daring. Barrows’ inability to have sex gives their relationship an unusual character and it’s clear that far from being a subservient woman, Parker is an equal in this partnership. In fact, she is the more sexually aggressive of the two and is arguably the spiritual leader of the whole group. For example, she’s the one who comes up with the scheme to humiliate the Texas Ranger and who insists on turning everyone around so that she can visit her mother. As I see it, even if it has been simplified considerably, this kind of psychological richness was only because the writing was based on a careful study of the real Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrows, making it more complex and more interesting film than it otherwise would be.

At the same time, this is also a film about the Depression. The Barrows brothers treat their robberies as their one path to earning money as they know no other while it’s doubtful whether or not Parker would have joined them had she lived in a hopeful time. Their antics like robbing only the banks’ money and never that of the customers make it seem as if they’re sticking it to the man rather than mere common criminals and win them the admiration of the downtrodden. One of the best moments is when Moss drives the injured couple to a camp of the hardscrabble poor who have evidently been turned out of their homes. Instead of being fearful, the camp’s residents appear awed by their notoriety and offer them food and blankets.

On balance, when it comes to directly comparing films in this genre, I find that I prefer Terrence Malick’s Badlands for better capturing the poetic escapism behind just giving up on the rules and laws of society and doing whatever you want. Bonnie & Clyde, fittingly, feels more like recording a slice of history. It’s worth mentioning however that Malick is considered a protégé of Arthur Penn, the director of this film, so the influence here is acknowledged. Still, this is a great film and very much worth watching.