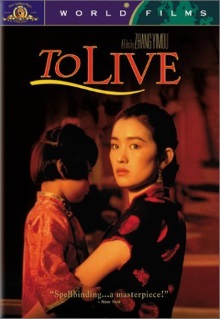

Continuing with our ongoing efforts to make a dent in our list of backlogged Chinese films, here is another entry from back when Zhang Yimou made films that mattered. Once again this one stars Gong Li plus a smattering of other familiar faces from that era. What marks a difference from the previous two films I’ve covered so far is that this one is actually critical of Communism, though the criticism is less severe than I’d expected.

Xu Fugui is the scion of a moneyed family in the 1940s but loses his family home due to his gambling addiction. Left penniless, he takes up performing in a shadow puppet troupe but is press-ganged into joining the Chinese Civil War. He survives only by performing for the Communists together with his friend Chunsheng. Following the war, he sees that the gambler who won his house from him is executed for being a member of the landowning gentry. After that comes the Great Leap Forwards when the citizens are all asked to donate all of the metal in their households to be smelted into steel. His son is killed in a freak accident during a visit by the District Chief to inspect their smelting work and it is revealed that the chief is none other than Chunsheng who is wracked by guilt. Flash forwards another ten years or so and it’s the Cultural Revolution and Fugui is forced to burn the shadow puppets he has kept for decades as everything that is old has been deemed counter-revolutionary. Each new era brings new trials for the family but throughout it all, Fugui and his wife continue to survive.

As usual, Zhang’s mastery of the basic skills of a director makes this a compelling watch and the performers are all consummate professionals. However I find myself less enamored of this film than the other great Chinese films of the 1990s. One reason for this is that all of them invariably cover roughly the same period of history so by the time I’m watching this one the subject feels overly familiar and it’s not as if To Live has anything dramatically new to say. The other is that this one has less of a unique theme underlying its narrative. To be sure, following a single family as it goes through the great events of the 20th century in China is always a worthy endeavor but not a particularly novel one.

More interesting is how this account of a difficult life presents a critique of Communism. After all, if Communism really did deliver everything that it promised, life would be easy for the common people and there would be no need to tell this story. The film doesn’t directly condemn Communism. The family is never directly the target of any of the various pogroms. But there is power nevertheless in the subtle ways that it undermines a rosy view of Communism’s role in society. The threat of persecution constantly hangs over the family even as Fugui goes to great lengths to ensure that they are perceived as being one of the common people while we see that even the most fervent loyalists are targeted, presumably because they possess some modicum of power. The way that everyone makes a great show of praising Mao Tse-Tung and declaring their loyalty only serves to show how empty those platitudes are.

Overall this is a fine film and I suppose it is an important one in the history of modern Chinese cinema. For me however the misery of the family is too diffuse and general to make it one of my favorites. There’s a reason why something like this is good but something like Farewell My Concubine is great.

One thought on “To Live (1994)”