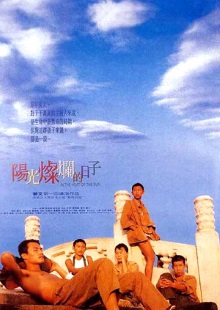

This marks the fourth film we’ve watched by director Jiang Wen but it was his directorial debut back in the day. As I understand it, this film garnered some controversy in its time but in an unusual direction. This film is set during the Cultural Revolution but unlike just about every other film portrayal of the event, it presents it as a mostly positive experience for its main character who seems to be a thinly veiled version of the director himself. This understandably ruffled some feathers of those who have painful memories of the period but contrary to my expectations, it is not in any way a sop to the Communist Party.

With his father along with many other adults being frequently assigned away from the city due to the Cultural Revolution, Ma Xiaojun and his gang of friends roam the streets of Beijing with impunity. They mercilessly taunt the teacher who has been assigned to teach them and to the frustration of Ma’s mother, he gets up to all kinds of trouble and doesn’t return home until late at night. After teaching himself how to pick locks, he takes to breaking into empty houses in the daytime. He doesn’t steal anything but instead rifles through their belongings as a sort of voyeur into their private lives. One day he discovers an apartment owned by a young girl Mi Lan and becomes captivated by the portrait of her he sees on the wall. He keeps a watch out for her and eventually does manage to meet and befriend her, calling her elder sister. She soon becomes a member of his regular gang. However Ma becomes frustrated when she becomes closer to the leader of the gang, Liu Yiku.

In the Heat of the Sun doesn’t ultimately do anything we haven’t seen before but it is rather shocking to see these sorts of themes being explored so frankly in a Chinese film. On one level it’s about a group of youths who experience their sexual coming-to-age while left to their own devices as their parents are away. To this end, the camera is unashamedly sensual as Ma fantasizes about Mi Lan’s body. Another girl Yu Beibei teases the boys as they are bathing naked in a communal shower, riding right on the edge of innocent fooling around and sexual foreplay. It’s tastefully done and there’s nothing lurid about it but I was still shocked to see it in a Chinese film. In effect, the film says that Ma has fond memories of the Cultural Revolution because it was like a long, extended summer for him during which time he had fun with his friends, enjoyed the best day of his life riding a bicycle with Mi Lan and perhaps discovered something about himself.

On another level, this is also a film about how memory is unreliable and that we often view our formative years through rose-tinted glasses. The narrator, meant to be the adult Ma but voiced by the director himself, warns that his recollections of that period is marred by bad memory and even his own tendency to present his past self in a better light. This explains various inconsistencies in the narrative such as how the character of Yu Beibei seems to disappear once Mi Lan becomes a regular member of the gang. I love how this accentuates how Ma’s perception of this period being the best time of his life may largely be a product of his own mind and whatever special relationship he may have had with Mi Lan may simply be an elaborate fantasy synthesized over time from his memories. We never find out how much of this is true but ultimately it doesn’t matter as these memories still shaped Ma as a person.

As we watch all this, the Cultural Revolution goes on in the background. Many other films of course have explored the cruelty, the hypocrisy and the tragedy of the period. In the Heat of the Sun doesn’t contain such critiques but in its own way, I feel that its barbs against the movement are no less sharp and are perhaps more original. The film portrays Ma and his friends as being thoroughly indoctrinated by the propaganda such that for example he dreams of a big war starting up so that he can win glory as a soldier. Yet the way they borrow the uniforms and medals of the adults to parade and dance in them is so irreverent and silly that it takes on a tone of mockery. Similarly one scene has the North Korean ambassador and his wife arrive for a Communist Party event but they turn out to be Chinese impostors who just want to watch the free performances. During a showing of the Soviet propaganda film Lenin in 1918 which they all know by heart, they sneak into a theatre to watch another film with nude scenes instead. So to Ma and his friends, the Cultural Revolution wasn’t sad but was a rather stupid and silly period.

As a coming of age film, I would rate this as being quite good already but with it being a Chinese film that portrays youths learning to be sexually aware, I am astounded by how daring it is. Its depiction of the Cultural Revolution is similarly innovative and incisive. This is sufficient to cause me to revise my opinion of Jiang Wen’s abilities as a director sharply upwards and it is a real shame that he isn’t better known internationally.