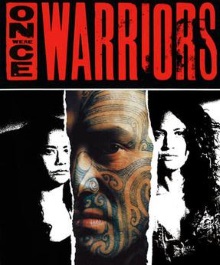

I’ve actually run into mentions of this New Zealand film more than once, on at least one occasion about how it is a realistic depiction of how a person’s personality can suddenly and shockingly shift under the influence of alcohol. This was director Lee Tamahori’s debut feature and he later went to make many well known commercial films in Hollywood but I don’t think that any of them has quite the impact of this one.

Beth Heke is married to Jake with multiple children and lives in a run down house in the city. Though they have genuine affection for each other, Jake is an irresponsible father and when drunk, is a horribly abusive husband. He is insouciant upon being laid off as the salary is only slightly more than the dole and regularly invite his friends to come over to his house to party, uncaring of how this disturbs the children. When Beth brings up the fact that the second oldest son Boogie has to attend court the next day for petty offences, Jake beats her bloody, claiming that she spoils the children too much. This leads Boogie to be taken away by child services. It is revealed that the oldest son Nig has already been driven away, choosing to join a Maori gang with a harsh initiation ritual. Beth is complicit in the neglect for a time, becoming drunk and participating in the parties. But she becomes upset when her plan to have the whole family visit Boogie falls apart. The breaking point comes when the next eldest child, 13-year old Grace, is raped by a guest in the house during one of Jake’s parties.

The whole film is an indictment of the lifestyle of a subgroup of urban Maori in New Zealand and that’s always tricky to pull off. This film deftly does this by making it a self-criticism of Maoris by Maoris when hardly any white people appearing at all and balancing it out with a strong affirmation of the positive aspects of traditional Maori culture. As such it focuses on individual choices and decisions and doesn’t consider the institutional causes of why so many Maoris end up living in this manner, while implying that the toxic masculinity evinced so so many Maori men is related to a corruption of traditional Maori warrior culture. There’s no doubting the powerful and visceral impact this film has, rooted in how deeply authentic and relatable it feels. This is helped by the viewer being able to see that Jake is, in a sense, a likable person. He is quick to anger and prone to violence, sure, but he’s also the picture perfect example of the friendly bro, the life of the party, a generally great guy to have around when you gather to sing and have a good time. Perhaps the single most devastating line in the film is Beth’s admission that she does indeed love Jake and that is the root of the problem.

At the same time, the film doesn’t hold back either when it comes to showing Jake at his worst. His savage beating of Beth leaves her with a horrifically swollen eye. He starts fights with random strangers and is proud of it. He even starts getting rough with Grace when he believes she is being disrespectful. This dual, no holds barred approach leaves you in no doubt that he is a horrible person yet it helps you understand why Beth finds it so hard to just leave him. As my wife notes, the rape scene is so much more horrible as the rapist is shown kissing and caressing Grace, as if to make it all better for her. All this makes Once Were Warriors an effective film that hits the audience hard, especially set as it is amidst an urban squalor that all of them regard as being normal.

Dark as the film gets, it perhaps isn’t completely realistic in how the portrays the government as being benevolent and Beth’s monologue at the end gets a little too on the nose. I also dislike how the simple act of moving back to the countryside is seemingly portrayed as a panacea for all of their problems and it’s strange how Nig joining a gang is something that is spun as being positive. I’d still rate this very highly for its personal account of abuse at home and for being as brave as it is for highlighting how some Maoris themselves are to blame for the awful lives that they lead.

One thought on “Once Were Warriors (1994)”