Our cinephile friend told us ages ago about the iconic scene from this film about a man trying to carry a lit candle across a courtyard. But it wasn’t until I watched the full scene that was included in the Jonathan Blow game The Witness that I bumped it up the priority list. I would say that rewatching the scene again here does lessen its impact but the whole thing is still an incredible triumph of the visual arts.

Andrei is a Russian poet who is in Italy to research the life of an 18th-century Russian composer Pavel Sosnovsky who has lived there. He is accompanied by a beautiful female Italian translator Eugenia but it soon becomes evident that they are interested in different things. Andrei is overtaken by a sense of melancholy and longing for his family and home as he comes to empathize with the depressive Sosnovsky. Eugenia however is entranced with idea of a romantic relationship with the poet and becomes increasingly unhappy when Andrei seems indifferent to her. In a town with a hot spring they meet a local crazy man named Domenico who is said to have once imprisoned his own family for seven years. Andrei befriends him and claims to understand his reasons for doing so. Domenico then asks him to perform a task that he has never been able to successfully carry out: to carry a lighted candle from one end of the pool to another, claiming that this will save the world.

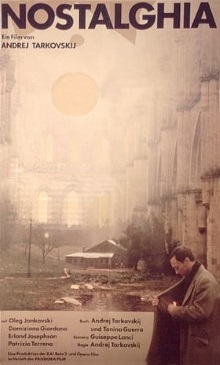

Like the rest of the works by Andrei Tarkovsky, this one is first and foremost an exercise of pure visual poetry. Even when seen on their own, shorn of context, the images are jaw dropping in their artistry and intensity. Plays of light and shadow, dimpled textures, the pervasive tendrils of fog and steam that drift across the landscape, striking compositions and much more are in evidence as Tarkovsky strives to make each and every frame beautiful. In fact, it is daunting to realize how much effort and coordination it must have taken to get everything set up perfectly. The rain that falls through the numerous holes in the roof of Domenico’s hovel of a house, the exact moment a lengthy camera shot ends with the characters looking up to catch the rays of the rising sun, even the movements of Domenico’s pet dog must have been carefully choreographed and I wonder how he managed to get that done. You can easily appreciate this film for its beauty alone and that is more than enough to qualify this for greatness.

Yet as my wife notes it’s one thing to be awed by the visuals and another whether or not the themes evoked here speak to you. I confess to being somewhat mystified by the depth of Andrei’s apparent despair. Unlike Sosnovsky, his wife and children are only plane ride away and he is temporarily in Italy by choice, not circumstance. Similarly it’s hard to sympathize with the mindset of Domenico and his insane rants about the end of the world. I get the sense that we’re supposed to perceive a twisted sort of greatness there but that’s not what I feel. I do rather like the side plot with Eugenia and how Andrei completely misses her point but it’s tangential and not something to get emotional about.

Unlike both Stalker and Solaris, Nostalghia feels both smaller in scale and ambition. The themes here are highly personal and specific to what I believe is a uniquely Russian mentality, which might explain why it seems to much less internationally popular than the other two films. Interestingly, it is also much less obscure and mysterious in its intent than the other two with Andrei’s dream sequences being easily interpreted as a sort of longing for his family. Without this mystique, it feels less grand but as I’m always suspicious of whether the mystique is simply hiding the lack of anything insightful to say, this might actually be the more grounded and mature film.