We’ve hardly watched any Danish films at all and this time we’re plumbing the depths of cinematic history for this very old film. What’s especially interesting is that this was made during the Nazi Germany occupation of Denmark and so the austere society depicted here can be interpreted as a kind of indictment against totalitarian rule. It’s also great how this film offers a very ambiguous morality that could really be read either way.

Anne is the young second wife to an elderly pastor Absalon in a Danish village in the 17th century. Absalon’s mother disapproves of her as Anne is younger than his son from his first marriage. Just as the son Martin returns home after a trip and is introduced to Anne, an older woman who has been accused of witchcraft begs for shelter but is quickly discovered and caught. She claims that Anne’s mother was herself a witch but was spared by Absalon out of love for Anne and threatens to denounce her. Meanwhile Anne and Martin predictably fall in love with one another as they are both of a similar age while Absalon is none the wiser as he deals with the threats of accused witch.

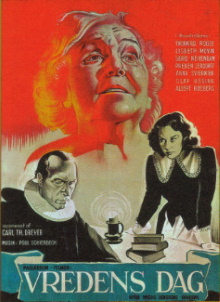

Between the black and white photography, the austere clothing of the people of the period and the plodding pace of the characters’ movements, this is film that looks and feels positively ancient. The plot is exceedingly simple and proceeds pretty much exactly as you would expect. Yet this combination actually boosts the film’s dramatic power. In a more modern film, it would be easy to interpret any such film as being an obvious indictment against a superstitious and cruel regime. Yet the witch trial is presented with such stately seriousness and the character of Anne is shown to be just malevolent enough in her own way that there is enough ambiguity here make things interesting. For example Absalon proves to have never asked for Anne’s consent before marrying her and later apologizes to her for it but neither is he shown to be cruel or domineering. Similarly none of the village officials who preside over the inquisition and the subsequent burning are hypocrites or sadists. They are all earnest Christians who appear to sincerely believe in the righteousness of what they are doing and that they really are saving the souls of the accused.

There are plenty of great touches heighten the atmosphere of fear and oppression. The invariably male elders of the community literally torture the accused witch on the rack and proudly congratulate each other on a job well done. Young children are gathered to practise singing a hymn that would accompany the actual burning. Everything is presented in such a straightforward way that it’s easy to believe that this is normal day-to-day life for them.

In the end it is still clear that the film is meant to condemn the witch trials and was apparently based on one of the most famous of such cases in Norway. Yet adding a touch of ambiguity to it makes the audience sit up and pay more attention as we try to work out what is really meant. At the same time, it is a dig at the Nazi occupiers that would be subtle enough to pass censorship. I’d consider this to be underrated, now largely forgotten film is well worth watching even today.