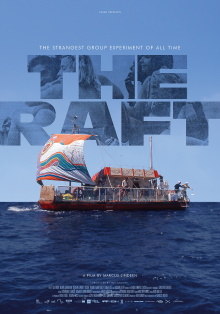

In all of my copious reading I believe that I have read about the Acali raft expedition of 1973 before and came away with the impression that it involved some kind of crazy sex cult. This of course is a complete fabrication on the part of the media at the time as this documentary by Marcus Lindeen makes clear. Using old footage, a wooden recreation of the original raft, testimony from participants who have survived until today and an actor reading from the journals of expedition leader Santiago Genovés, this film presents a surprisingly positive take on what happened.

As Genovés explains it, he is an anthropologist specializing in human violence and after being caught up in a plane hostage taking crisis, he realized that keeping a group of people trapped together would make for a good experiment about aggression. To that end, he has a sailing raft, Acali, built and auditions a crew of ten women and men to join him on a voyage crossing the Atlantic Ocean, lasting about three months. In order to foster tension and animosity, he deliberately chose attractive and young crew members of varying ethnicities and nationalities and even places the women in positions of authority. For example, the only one of them with sailing experience and training is Maria Björnstam of Sweden who is the captain. All of them sleep in a single large cabin and Genovés has them fill out questionnaires asking provocative questions like which other crew member do they dislike the most and who they would like to have sex with.

All this sounds like a disaster waiting to happen and seems totally unscientific as it would virtually impossible for Genovés to make any kind of objective observations given he is very much a part of this social group. His very attitude itself is biased as he hopes that sexual tension and jealousy among the crew will lead to conflict and eagerly looks forward to every disruption in the daily routine as a sign that violence is about the erupt. All this is revealed both through Genovés’ journal and the recollections of the crew members who are still alive today as they explore the recreation of the Acali and let it spark their memories. I particularly enjoyed the details of their routines, such as how they go to the toilet while onboard, and how they find little spots and opportunities for privacy and just to vent by themselves aboard the cramped confines of the craft.

Yet the wonder of this experiment is that despite Genovés’ worst provocations, the group never breaks down. Even as the days go by and people grow bored, they continue to work well together and are in high spirits. The sole exception is Genovés himself who grows increasingly upset that his theories are being disproved and whose authority and poor attitude is resented by everyone else. Also fascinating is that while the participants do have sex, there seems to have been far less of it than people imagined. As the survivors explain in this film, conditions on the raft were so cramped that having sex was awkward and embarrassing. It is telling that they all seemed to have enjoyed their experience on the raft and regard their time on it as a treasured memory.

Of course, one must always be mindful of bias. It’s clear that filmmaker Lindeen thinks very little of Genovés and I note that out of all of the surviving crew members, only one is male. It’s possible that the other male participants may have remembered the events differently had they been interviewed. All the same, I see no reason to doubt this account of the experiment and I confess that I found the conclusion it reached to be hopeful and uplifting. While dramatists love to bemoan how often humans fight one another, scientists know that the high degree of cooperation and tolerance between individuals of the human species is unusual among all species on our planet. It’s great to see that playing out in real life, even against the wishes and expectations of Genovés.