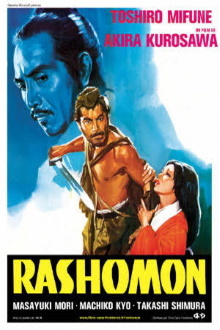

Given that Akira Kurosawa has never done wrong by us yet, it’s likely that we’ll eventually get around to watching all of his classics. This particular title well deserves that status as it was one of the first Japanese films to win international awards and indeed its name is now used in the common term the Rashomon effect to describe the unreliability of witnesses and mutually contradicting accounts.

One rainy day, a woodcutter and a priest, later joined by another peasant, gather to tell the story of a killing in the woods. The woodcutter was the one who found the corpse and was called to the court to testify. The bandit accused of the crime was caught and is the first to tell his story. He recounts that he was lazing in the woods when a samurai and his wife walked by. Out of lust for the woman, he tricked the samurai and was able to tie him up. The wife tried to resist him at first but eventually succumbed to his seduction. He claimed that he was going to let the samurai live but the wife, out of shame, forced the two of them to duel and so the bandit killed him over the course of an epic fight. But when the wife who later ran away tells her version of the events, it is dramatically different. Even the deceased samurai gets to tell his story as his spirit is channelled through a medium. The peasant takes the lies as proof that humanity is selfish and dishonest even to themselves, driving the priest to despair.

As befits the work of a true grandmaster of cinema, it is astounding how Kurosawa is able to achieve so much with so little. This is a relatively short film, shot with only three sets and a handful of actors. Yet every part of it is just exquisite, the artfully ruined Rashomon gate in the rain, the music that faithfully follows every beat of the story and each of the characters’ movements, the use of light filtered through branches and so on. I especially loved the dramatically different accounts of the fight between the bandit and the samurai. As the bandit tells it, it was an epic fight in which they crossed blades many times in a display of skill, wits and luck. But as the woodcutter later tells it, both were terrified of the other and only weakly and clumsily poked at each other with the final result with completely a matter of luck. I thought it was great that Kurosawa shot the first version as a well choreographed fight that nevertheless still seemed plausible and realistic, with exciting turnarounds and desperate plays. Yet when you watch the second version, you immediately realize that this should be typically what really happens in real life.

Contrary to what some commentators stated and how some other works choose to incorporate the idea of contradictory witnesses, I feel that there is no real ambiguity in Rashomon at all. Indeed I find that Kurosawa prefers that things are always clear to the audience in all of his works and in the instance, it is the last testimony that is the obvious truth despite the fact that the woodcutter left out one key detail. Each of the characters is perfectly predictable in how they twist their individual stories, reflecting idealized versions of themselves. This means that even while each character tells lies, Kurosawa is actually establishing that we can indeed tell what the real truth is by examining their motivations. This is quite different from later uses of the Rashomon effect which often take the opposite tack: that due to the subjectivity of human recollection, it is often impossible to establish any truth at all. I believe that even the original short story this was based on was much more ambiguous. This also reinforces how Kurosawa is rather American in his outlook and quite optimistic.

All in all, this is another great film by Kurosawa and I really do love how compact and yet impactful it is. In terms of ideas and themes, it has of course been matched or surpassed by other films, but it remains an incredible exemplar of refined cinematic craftsmanship.

One thought on “Rashomon (1950)”