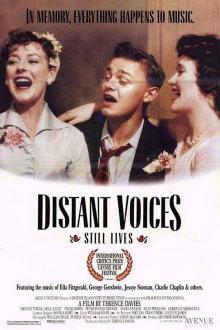

At about the same time last year, both of us were completely awestruck by the emotive power of Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City. Distant Voices, Still Lives is one of his earlier films and it is also essentially about growing up in the city of Liverpool. Whereas the documentary dealt with the city as a whole, this one focuses on one particular working-class family in the city in the 1940s and 1950s and we all understand that this is at least loosely based on Davies’ own life.

There’s no central narrative here. Instead, the film consists of fragments of the lives of the family, freely skipping back and forth in time. The father has a violent temper and abuses the rest of the family, yet he still has his tender moments such as when they celebrate Christmas. The children, two girls and a boy, are thoroughly cowed by him and frustrated by his refusal to show any affection. Yet in time after the father passes away and the children grow and get married, there are signs that their new families follow the same, well-established pattern. All this is presented primarily through singing as the various characters enjoy themselves by breaking out in song. In this way, the film shows them doing chores, living through the Blitz, growing up and going to work, getting married and so on.

Once again this is an intensely personal project on the part of Davies and is obviously autobiographical to a large extent. Much of its impact is therefore lost on us as most of the historically accurate details such as the architecture and layout of the houses, the music of the period, their clothing, their language and manner of speech and even the impressively large variety of alcoholic beverages they indulge in can hardly be expected to resonate with us Asians. Still, it is a lot of fun to recognize songs that we’ve never heard in ages, such as Buttons and Bows. But even viewed at such a remove, the love and care that went into this film is plain to see. It serves as a valuable ethnographic record of the people of the era and that is something that all of us can appreciate and enjoy even today.

I still like Time and the City more for its grand sweep of history and I suppose the poetry used there speaks more to me than the music here. But this is genuinely a masterpiece as well. Perhaps what I love most about it is how it fully embraces the contradictions of emotions. Just as the family’s children do miss the father after he passes away despite his temper and habitual abuse, so too does Davies express a fondness and powerful sense of nostalgia for his childhood, while acknowledging that the brand of dominant masculinity that runs in those families would be considered toxic today. It’s so refreshing how Davies can capture so much of his love for his people in this film while being completely honest about their shortcomings.