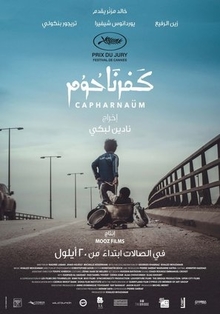

I’ve had in my list for a while now but the huge explosion that took place in Lebanon earlier this year sure added extra impetus to get around to watching it. This is a harrowing film, about a child who is forced to fend for himself on the streets of Beirut, was made by Nadine Labaki, a Lebanese director. That kind of matters because no foreigner could make a film like this with such moral authority. Also, this film was apparently a huge hit in China, of all places.

12-year-old Zain is the eldest child in a family of many siblings, all of whom live under atrocious conditions being born to neglectful and uneducated parents. He works for Assad, a local shop owner who is also the family’s landlord and has never been to school. When his sister Sahar gets her first period, he helps her hide it, suspecting that their parents will marry her off to Assad. Indeed they do so despite Zain’s protests and as Sahar is dragged off, Zain runs away from home. He wanders around for a while and lingers around an amusement park that he finds but is unable to find any employment. Fortunately a young Ethiopian single mother Tigest takes pity on him and takes him in. Zain helps her take care of her baby while she works at the park but Tigest has problems of her own as she is an illegal migrant and struggles to save enough money to have fake documents forged.

This is a plot-heavy film that is packed so full of tumultuous events and detail that it’s almost overwhelming. Everything from vans packed so full of children that their bags must be hung outside to how the parents teach their children to help them soak clothes in drugs which are then smuggled into prisons, ring with authenticity. There is so much tragedy and squalor that I would ordinarily dismiss it as being misery porn. But as my wife notes, this film distinguishes itself by choosing not to dwell on and hence dramatize the suffering as so many such films do. Instead, it takes on a matter of fact stance, as if saying that this is simply what daily life in the poorer parts of Beirut is like and it’s bad enough that it speaks for itself, and that makes it more convincing than if the director kept trying to tug at the audience’s heartstrings. Of course, this isn’t actually a true story and Zain is too savvy and determined to make for a realistic character. Yet there is so much detail here that it’s easy to believe that this is a collage of all kinds of lives and stories from the real Beirut as the director claims. It helps as well that almost all of the performers in it are amateurs and many including Zain Al Rafeea who plays Zain are real refugees. It is astonishing how the director was able to coax such amazing performances from them, and that is including the baby!

I am however more impressed that all this effort is tuned to express a single bold and cohesive critique. This film isn’t just bemoaning poverty and child neglect in general in Lebanon, it very specifically blames this state of affairs on parents who keep having children while not having the means to support them. By putting the accusation in Zain’s mouth, the director’s intent could not be more clear or more stark. Yet those in the dock are not Zain’s parents alone, but the wider culture and perhaps even the religion itself that forbids abortion or birth control and finds virtue in the act of having as many children as possible. Arguably the film is saying that the entirety of Lebanon is guilty as the locals are apathetic to the sight of the obviously distressed Zain wandering the streets, sometimes towing an infant behind him. It is telling that it falls upon Tigest, herself a poor and powerless migrant, to take notice of him and his plight. This is why I believe it would impossible for a foreigner to make this film. Only a Lebanese would have the moral authority to make this incisive an accusation. In the film, things end well for Zain and the full apparatus of the state is eventually deployed to investigate his case. Yet that is only because Zain is clever enough to gain the attention of the media while untold numbers of similar children languish in similar straits with no one to help them.

Many films attempt to take up the cause of the downtrodden but rarely do we see one that is as clearly drawn from the director’s own lived experience. Have you ever wondered what the inside of a Lebanese prison looks like or how half a dozen children share a single mattress or what a mother does when she has no food for her babies? This isn’t the work of some well meaning outsider who has to reach in search of dubious examples of misery. This looks and feels like something that comes right off of the streets and that’s makes it one of the most powerful activist films I’ve ever seen.