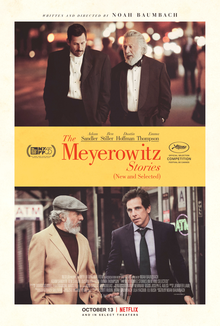

This came out a little earlier than Marriage Story but we’ve only just now gotten around to watching it and having done so, it’s clearer than ever that Noah Baumbach is the modern Woody Allen. He’s in that sweet spot now where multiple big Hollywood stars are willing to sign up to act in small roles in a relatively low budget film just due to his growing reputation as a director of dialogue-heavy drama who gives interesting characters for actors to engage with. This film is a particularly good example with its multiple interwoven stories.

The stories revolve around the family members of Harold Meyerowitz, a retired art professor in New York, and a sculptor who never quite made it big. His eldest son Danny is unemployed as he has been a house-husband and is now trying to find her bearings as he is getting divorced. He does have a close relationship with his daughter Eliza who is an aspiring filmmaker. Meanwhile as Harold has been through four wives, his half-brother Matthew is a successful financial advisor who has established himself in Los Angeles. Finally there is the half-sister Jean who is constantly in the background unremarked by anyone. All three wrestle with their mixed feelings for their father who is self-centered and seems to be resentful that his art never took off. Danny and Matthew also have a tense relationship as Matthew is wealthy and enjoyed more attention from Harold when he was growing up and Danny feels that he was forced to give up his own interests in music due to his father’s inability to be nurturing.

This film hits the ground running with a surfeit of dialogue and non-stop introductions to new characters. Yet such is Baumbach’s mastery of the form that we’re always able to tell who’s who and what is going on. The dynamics of the relationships are riveting, the dialogue is punchy and the characters are all interesting. None of the themes here are new: a father who never listens to what his children are actually saying or what they really want; children who in turn long to escape from his influence and yet still find themselves being drawn back again and again; siblings pointlessly jealous of each other for having received special attention while growing up and so on. Where this film excels is its near perfect execution enabled by great performances by an all-star cast. It’s amazing to watch Dustin Hoffman return to the screen but of course it is Adam Sandler’s performance that has wowed everyone. Not only has Baumbach successfully convinced Sandler to actually act in a serious role but he has put him into a sort of middle-aged, embittered version of the man-child type characters the actor has become associated with. That’s just one of the strokes of genius that makes this such a stand out film.

As with Marriage Story, Baumbach creates stories about the milieu that he knows, in this case the creative art set of upper class New York. However it does feel less egregious here as this story depends on Harold being at least a moderately decent artist and his children being brought us in this setting. One oddity however is the film’s treatment of the sister Jean who story seems underdeveloped and yet the director deliberately points that out by having the brothers ask her why she is always just around despite how little attention Harold seems to give her. In her first appearance, she actually seems to be hiding away while all of the other characters are being introduced to one another. It feels like a private joke of some kind as the director even gives her her own title card without really giving the space for her own story as the focus remains on the two brothers during what is supposed to be her segmen. But if that’s the case, I don’t see what purpose it serves.

Overall this is another fine film by Baumbach and I think it is safe to say that we will be watching plenty more of his work in the years to come. One thing that I have grown to like about his characters that they feel refreshingly honest, without any of the fake self-deprecation that Woody Allen relies on so heavily. Here Harold is the same man that he has always has been and isn’t the least self-conscious of it but it is his children who must come to terms themselves with the kind of person their father is.