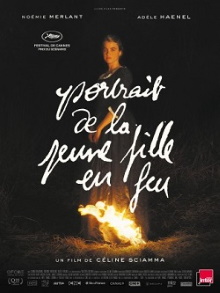

I rated director Céline Sciamma last film Girlhood as being well-intentioned but having problems with authenticity. This one is another all women film about women’s lack of power to make choices about their lives, this time taking place in late 18th century France. The story was written by Sciamma herself and isn’t based on anyone’s life but it’s the more poignant, powerful film for me.

Marianne, a painter by trade, travels to a manor on an island off the coast of Brittany. She has been hired by the lady of the house to paint her daughter in the hopes of using it to secure a marriage with a Milanese nobleman. However the maid Sophie reveals to her that another painter has already tried and failed as the daughter Héloïse refuses to pose to be painted. She also learns that she has a sister who recently committed suicide. Both sisters were until recently living in a convent and feared being married off to an unknown man. The mother explains that Héloïse will be lead to believe that Marianne has been hired as a companion and that the latter must therefore paint her in secret. As the two get to know each other and spend time on the island, Marianne tries to commit her features to memory and paint her at night. As their feelings for each other grow, Marianne feels guilty about the deception, especially once she realizes that the mother is so intent on marrying off her daughters because she herself is Italian and desperately wishes to move back to Milan.

This film looks a little underwhelming at first and I was a little leery of it going for the expected route of a romantic relationship between Marianne and Héloïse. I was quickly won over by the multiple angles that it takes on its theme of women not having power over their own lives. This story isn’t just that of the two as it is that of Sophie the maid who we later learn is pregnant and wants to abort the unwanted fetus. It is also about Marianne’s career as a painter. As she explains, to get work she must adhere to established conventions of what is expected of her. Furthermore, as a woman, she is not allowed to learn to paint nude men and this bars her from making the kind of art that is traditionally considered great. That the person who is forcing the marriage on Héloïse is her own mother makes it even more powerful. All too often it is women themselves who are the gatekeepers who enforce the rules and norms of the world of men on other women. This is reinforced in the film when the mother leaves and in her absence the other two girls treat Sophie as a friend and equal instead of as a lower class servant.

The cinematography is excellent throughout and as my wife notes, the color palette seems to have been carefully chosen to evoke paintings. Scenes like that of Marianne and Héloïse reading Orpheus and Eurydice from a book to Sophie work on many levels, showing how they treat Sophie as an equal and also is used to reference their own relationship later on. When they witness Sophie get an abortion, Héloïse invites Marianne to paint the scene without needing to say so, a clear rebuttal of the male-centric tradition of what constitutes great art and a taboo that is arguably more profane than even their burgeoning lesbian relationship. Héloïse herself is revealed to be just as much a pawn of the system of the world of men as she yearns most of all to return to the Milan that she remembers from her childhood and presumably was brought to Brittany through marriage herself. There’s just so much packed into this film that you can find themes and meanings in every corner that you look, all of it exquisitely crafted with great care and attention.

About the only thing that makes me a little disappointed with this is that people seem to characterize this as being mainly a lesbian romance film when it’s really so much broader and richer than that. It easily qualifies as one of the best films I’ve watched this year and so earns a hearty recommendation.

One thought on “Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)”