Given the title and the poster, you might expect this to be another nature documentary. In fact this is more about the people who live in the Antarctic stations, particularly those who endure a full year there through the dark winter season, isolated from the rest of the world. Given that I’ve previously worked in remote locations as part of the logging industry, this had added resonance and I really enjoyed the details of what they daily routines looked liked.

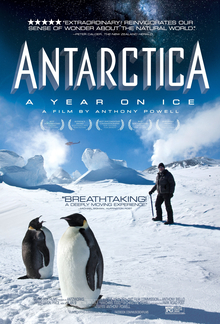

This film was made by Anthony B. Powell who has contributed footage to noted nature shows before but whose day job is a communications engineer. It documents a year spent on Antarctica, focusing mainly on the US McMurdo Station and New Zealand’s Scott Base. The year begins with the batch of new staff arriving by plane in the Antarctic summer in October when the sun never sets. It gives us a tour of the bases and the area surrounding them and through interviews with the staff, gives us an idea of what their work consists of and what it feels like to live there. Most of the staff leave before the onset of winter however when there is no sun and temperatures plunge even further. Those left behind must cope with the isolation and extreme cold but also find joy sights to be seen in the night sky in the form of the auroral lights. Then as the winter ends, and cargo ships return to resupply the bases and contact is reestablished, the cycle begins anew.

We’ve watched plenty of nature documentaries before and they’re almost always great but this may be the first time we’ve watched one that is about the people who choose to work in the remotest corners of the Earth. What’s even better is that the people being interviewed here aren’t really the scientists and researchers but their support staff. These are the engineers and technicians who maintain the equipment, the helicopter pilots who carry them, the storekeeper who keeps inventory, the fire station staff who are there in case of emergency, even the cook who makes sure everyone is fed. All of them are frank that they’re mostly there to do their jobs and it can be surprising how little opportunity there is for them to see much of Antarctica beyond their assigned stations. But for whose to chose to stay over for the winter, especially those who do it year after year, it is also because they’ve proven to be psychologically capable of dealing with the darkness and the isolation and perhaps even prefer it. It is very satisfying to watch these profiles of people who are mostly ordinary but maybe a little more open to adventure than most, complete with all of the small details of their lives there.

As you might expect, a documentary like this can boast of some truly outstanding photography of the amazing sights to be seen, courtesy of special equipment that Powell apparently constructed for himself. But there are also plenty of shots that are effectively of home video quality and that adds a sense of reassurance and authenticity that these are real, ordinary people. It’s pretty amazing to watch video contributions from the bases of other countries of the antics that they get up to and this film includes a wedding ceremony of Powell marrying his wife who he met while working there. Even a simple shot of their cafeteria filling up with people eating engenders emotions as you comprehend that this is a slice of mundanity while there might be a raging storm outside and that this might be the only form of civilization alone in the great vastness. It is a similar sort of feeling as when you’re in a remote camp in the jungle or a hiking camp up in the mountains, but I would imagine to a far more pronounced extent and isn’t there a kind of special magic in the “wow, I can’t believe I’m actually here” sense.

All this means is that while there are probably many more beautiful shows about Antarctica out there, this one feels special to me because it focuses on the people rather than the place itself, whose work makes such things as even documentaries possible. About the only criticism I can think of is that this film downplays the risks and the costs of maintaining this highly select group of people under such hostile environmental conditions. It’s one thing to argue that the risks and costs are justified but it would still be only fair to confront them directly.