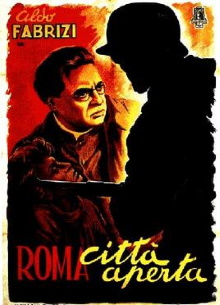

This marks the first film we’ve watched by legendary Italian director Roberto Rossellini and part of his so-called Neorealist Trilogy, so named because they most use non-professional actors. While it is solid work, I didn’t find it particularly noteworthy because we’ve seen so much like it already. What is remarkable is that this film was made just one year after the real events it depicts about a Rome under German occupation, and hence the difficult conditions and crude production quality were due to the very limited resources available to the filmmakers.

In 1944 Rome, German Nazis and Italian Fascists cooperate to root out the leaders of the Resistance. Foremost among them are Giorgio Manfredi, a leader of the Communists who flees to the home of Francesco, another Resistance leader. Francesco is due to marry Pina, who is also active in the Resistance. Another member of their cell is Catholic priest Don Pietro Pellegrini who is tasked with sending money and messages to a group of fighters outside of the city as the Gestapo is now actively looking for Manfredi. It turns out that even the children, including Pina’s son, are fighting against the occupation forces by sabotaging equipment without the knowledge of the adults. When the Nazis mount a huge raid on the building where Francesco and Pina live, Pina is killed the day before her wedding as she protests Francesco being captured.

It’s a little difficult at first to understand who’s who as there are multiple Resistance factions but soon enough you realize that this is a straight take on the activities of a Resistance cell in Rome with no dramatic twists whatsoever. This view of their daily lives and activities is as constricted as the occupation is so there are no wide, sweeping shots of the city. I suppose it’s also because they’re working on such a limited budget. It shows their routines, mixing daily needs and resistance activities, on an intimate level. What stands out here is the low-key, undramatic nature of most of their work, carrying money hidden in books, passing messages, up to hiding weapons. We also see their privation, how they have limited food and use ration cards, but even here the film’s doesn’t dwell on their misery. All this is presented in a very matter-of-fact, understated, way, which is probably why this was later called Neorealism. In a more commercial film for example, the actress who plays Pina would have been more beautiful but here she is played by a rather plain-looking woman. This is a film that strives for authenticity almost as if it were a documentary.

There are some interesting themes here such as having a Catholic priest cooperate with a Communist against the Nazis but on the whole I feel that this film is too straightforward to be really interesting to me. The worst excesses depicted here actually feel tame by modern standards. In one scene, the Nazi interrogator tells the priest that the brutality that they are willing to go to will exceed his imagination and the priest replies that they underestimate his imagination. Unfortunately we in the present day don’t need our imaginations to know that interrogations and oppression are so much worse now. Similarly the situation we see here in Rome was bad but we also know how much worse things were elsewhere in the world during the Second World War.

On the whole this is a solid, well-made film but it doesn’t strike me as being anything more than that. The production difficulties that it experienced makes it look gritty in a way that doesn’t seem to elevate its visual appeal and its characters are in the end just not that interesting. To me it has historic value being made so soon after the end of the war that it can capture, in situ, what it was like but watching it in the present day is just not a very impressive experience.