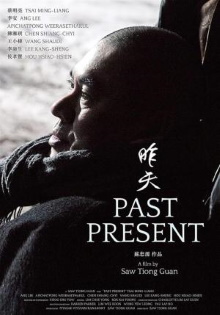

The last and easily my favorite of the Isle to Isle documentary screenings is one about Tsai Ming-Liang, perhaps the most renowned director to emerge from Malaysia though he is probably considered Taiwanese by now. Pleasingly this one was made by a very young filmmaker who is himself Malaysian Saw Tiong Guan and focuses largely on Tsai’s childhood in Kuching, Sarawak. By pulling on the nostalgic power of old music and shots of Tsai walking the streets of Kuching, this documentary consciously strives for, and somewhat achieves, the atmosphere of Tsai’s own films. This makes it one of the most effective documentaries I have ever seen.

Once again, this is the kind of documentary that plunges right into things without feeling the need to explain who Tsai Ming-Liang is. The director recounts his experience of growing up in the much more permissive environment of the 1960s in Kuching, Sarawak. He also shows how his lifelong passion for film was kindled by his grandparents who would repeatedly take him to the cinema, sometimes to watch the same film twice in a day, even at the expense of his studies. It even ties in with developing his creativity as after he is deprived of these experiences, he would imagine elaborate scenarios of running away with his grandfather to the cinema. Naturally it also features interviews with interlocutors who speak highly of Tsai’s work, most notably fellow directors Ang Lee, Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Lee comments for example that Tsai is a stubborn director who knows what he wants to do and can’t be dissuaded with any amount of money offered. I also really liked how it talks about some of Tsai’s forays into art installations and how it is really a natural outgrowth of his previous work in film.

This documentary has zero value to anyone who has not watched and loved a film by Tsai and rightfully assumes that everyone watching this already knows what it’s about without wasting anyone’s time on pointless fluff. To those who are fans however, this is an incredibly dense and rich source of information, so much so that it’s a little shocking how much of himself Tsai bares to the public. Watching this, you gain genuine insight into his creative process and how deeply his films draw from his own life. It’s amusing how his long-time muse Lee Kang-Sheng comments that he gave up reading Tsai’s scripts ten years ago as what matters are his moment to moment direction. Behind the scenes shots of his sets also shows how much importance he places on physical acting over dialogue, treating the actors more like dancers. Tsai acquits himself well through these conversations. While he is clearly someone who is moved by nostalgia and has a strong emotional attachment to old objects and the history that they possess, I appreciate how he doesn’t seem to reproach anyone as he accepts that change is an inevitable part of life. It strikes me that he understands that he is a person of his era and he realizes that someone born later would know a completely different Malaysia and that’s fine too.

At the same time, this documentary reflects its maker’s own preferences. It is evident that of the themes that are present in Tsai’s oeuvre, it is his love of old cinemas that resonates with Saw most. You can perceive that from the extracts of scenes from Tsai’s films that he chooses to highlight here and the overall emphasis on Tsai’s childhood. Yet someone else might choose to highlight other themes that also recur in Tsai’s works, such as the alienation of the individual in the city or the forbidden fruit aspect of sexuality. That too is fine but it does indicate that Tsai’s works are richer than can be covered in this one documentary. I do see Saw as someone who understands Tsai’s films intimately. I loved Chen Shiang-Chyi’s comments on how even though there is little dialogue everything else about the scene can be perceived as speaking to the audience, from the sounds of a character’s movements to even the emptiness itself. Watching this it struck me that while some great directors are known for their mastery of light, Tsai’s usage of empty space is especially notable.

Finally, as a Malaysian it is amazing to watch how interesting it makes the city of Kuching look and how by following Tsai as he shows us the streets and landmarks he has known as a child, this documentary copies some of Tsai’s own visual style. The film is absolutely packed full of interesting information and insights, wasting no time at all, and it really does tell you a lot more about Tsai beyond just the superficial basics. I suppose that other documentaries can be judged better on the basis that they’re about weightier subjects, and this is after all merely about the life and work of one director. But I do have to say that this is now of my favorite documentaries ever.