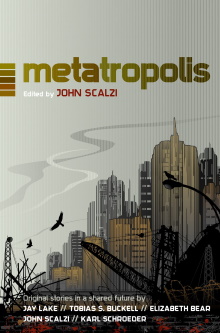

This anthology has an interesting backstory in that it started out as an audiobook project that was only published as a written book as something of an afterthought. This is also a shared world project as the five different writers including editor John Scalzi worked together to create a world about rebuilding civilization after an ecological and economic collapse and then each wrote a story set in it. The appeal of this is immediately obvious to someone like me, especially as I’m always on the lookout for stories that purport to show what a post-capitalist utopia might look like on a day-to-day basis. Unfortunately I found this collection to be mostly a disappointment, filled with the usual shallow critiques of capitalism and a description of the economic activities of the post-revolutionary world that feels oddly old-fashioned now only some ten years after it was published.

Between climate change, economic collapse due to massive wealth disparities and the complete breakdown of fossil-fuel powered industry, civilization as we know today it has ended. This collection of stories offers some answers to might come after and it’s admirable that this series explicitly make an effort to avoid being all apocalyptic gloom and doom. Jay Lake’s In the Forests of the Night describes a community of tree-huggers, literally so as they hide under the canopies of the forests of Cascadia on the western coast of North America. They do so to avoid the surveillance and attention of the weakened but still significant remnant corporate and national powers. Cascadiapolis is effectively its own polity, running an eco-friendly economy and is font of scientific wonders, especially in the life sciences, due to the brilliant minds who have flocked to it. Unfortunately while they make an effort to ensure their own security, their societal organization idealizes anarchy and is thus inherently vulnerable to infiltration.

The plot involves Cascadiapolis being infiltrated by two foreign agents. Interestingly one of them is very much a John Galt-like figure and I think the resemblance is too uncanny not to have been deliberate. He actually embodies the values of the community even more than any of its natives but knows that Cascadiapolis itself must be destroyed to allow its seeds to flourish everywhere. I’m not confident that I understand that everything that happens in this story as its ending seems open to interpretation, but my best guess is that there is enough left of the original US government to resent the existence of a rebellious state within its borders. The next two stories Stochasti-city by Tobias Buckell and The Red in the Sky is Our Blood by Elizabeth Bear are also ultimately about forming new separate societies within what was once the US. However instead of building them out in the wilderness, these ones are set in the hollowed out cities of the old world themselves, taking over abandoned skyscrapers to be turned into vertical farms and warehouses into community living spaces. The plot for the latter is almost irrelevant but I did rather like the story of the former, about a bar bouncer being hired to manage an insurrection through a crowdsourcing temporary work assignment app.

All three stories rely on the usual, common critiques of capitalism that are demonstrably false. An easy example is the old bugbear that corporations are so focused on turning a profit every quarter that they are unable to allocate capital to long-term projects. In the real world, it’s more likely that the opposite is true as investors seem happy to throw money at projects that sound cool but have little realistic chance of turning a profit in the predictable future. Or just study the history of a company like Tesla and see how long it took them from founding to selling their first car and how it long it took from there to actually making a small profit compared to their massive invested capital. Similarly in two of the stories, the activists have to seize control of the abandoned buildings they want to use through subterfuge or force and this forms the main plot of the stories. They are unable to buy them as the corporations that own them will not let them go for any reasonable price even though they are not being used. Again, this isn’t at all like what we see in reality as capital write-downs are common and most owners of unused or abandoned buildings will usually be quite happy to let them go at cheap prices. In the real world, anyone who comes up actionable ideas to turn unproductive assets into productive ones and seems committed to actually carrying them out will quickly find themselves flooded with offers to fund them.

That’s why of all the stories here, I think I like John Scalzi’s own contribution Utere nihil non extra quiritationem suis the best. As he admits, he feels that he needs to spackle over the holes in this shared world and as such his story is set within the walls of an utopia but from the perspective of an underachieving slacker who takes its safety and prosperity for granted. His New St. Louis is a carefully planned city designed to have zero net ecological impact and uses only energy credits in its internal economy. In exchange however all residents must take up a job as assigned by its governing authority and this is walled city that keeps non-residents out. Of course Scalzi still comes down in favor of this post-capitalist community so his protagonist learns to appreciate his city. But he is clear-eyed about how it survives only due to technological superiority and by strictly rationing the community’s resources to those who are willing and able to contribute back.

The last story Karl Schroeder’s To Hie from Far Cilenia features the coolest use of technology. In this case augmented reality headsets overlay exotic virtual worlds on top of physical reality and these worlds have their own politics and economics. What happens in these worlds matters in real life as in the story an old cache of plutonium is stolen and the authorities must track its movement through one such virtual world. It’s a decent high-concept premise and I was excited about seeing what it would do with AR. Unfortunately it isn’t clear to me how this is any different from being just a secure, specialized communications network. Any thing that happens in here happens in the real world too, for example they have doors and passages that appear in the virtual world and not the real one. This is simply explained by there being trick doors with hidden activation mechanisms that can’t be seen in the real door but they’re still real physical objects. Even the story’s conclusion somewhat undermines its starting premise: the plutonium is very real and no amount of obfuscating layers of the virtual can change that.

After all this, it’s not hard to see what this volume was so disappointing to me. It’s easy to see how the writers mostly come from the same circles and spaces and envision the same kind of utopia: distributed cottage industry, low population density, eco-friendly, using bicycles instead of cars etc. But I’m not convinced that the writers really understand economics or what it actually means when one method of production is more efficient than another or why economies of scale matter. It’s also striking that when they describe productive jobs, it’s all couriers and spotters and drivers. That’s another reason why I like Scalzi’s story the most as it accepts that pig farming is necessary and then even something like that requires significant infrastructure. It’s not all: we will live among the trees and live well but be almost invisible both from sight and from our ecological footprint. How do they possess seemingly infinite processing power without the chips that come from massive fabs? Where does the feedstock for their ubiquitous 3D printers come from?

Finally this volume feels particularly outdated because the developments of the Covid-19 pandemic have changed the real world in ways that are perhaps even more exotic than the writers here have envisioned. For all that they value eco-friendliness and a low-energy use economy, the characters in these stories sure do need to physically move around a lot. Maybe because each person sitting and staying at home while freely interacting with the rest of the world in all kinds of amazing ways doesn’t sound like an exciting story or living a worthwhile life. Similarly it doesn’t seem like there’s anything really fascinating about the topology of a virtual world changing all the time compared how static real world geography is. Isn’t the equivalent simply what’s trending on Twitter for example and people redirecting their attention and energies accordingly? A single person can wear multiple identities online as they work from home and the addition of AR technology doesn’t fundamentally change that. The writers seem to disfavor globalization because moving goods across the world seems expensive in terms of energy and harmful to the environment. But it seems like having the people stay put and the goods move is actually better on both counts. Food for thought.