This Hong Kong film is partially based on a true event involving government workers clearing the shacks of homeless people in Sham Shui Po. For a while I was inclined to dislike it as it seemed like an overly sentimental take on a complex issue, falling into the trap of the recent spate of Hong Kong films that are well-intentioned but simplistic. Then I realized that the opinions of its main character might not be the film’s own opinion and indeed some of the other homeless people call him out for his stubbornness. Perhaps director Jun Li might personally be more sympathetic to those views than I’d like but at least he proves that he has thought through it carefully and that makes me feel a lot better about this film.

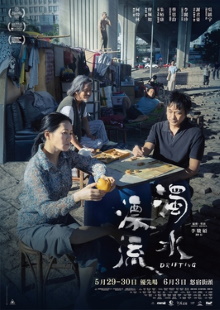

Upon release from prison for some unspecified crime, the homeless Fai returns to the streets and is immediately treated to a hit of drugs by his friend Lou Ye. Soon afterwards street cleaners accompanied by police arrive to dismantle their cardboard shelters without giving them a chance to retrieve their belongings. The small group of homeless people scavenge building materials to build new shelters under a flyover in an area that is still being developed. A social worker Ho who habitually helps the homeless helps them sue the government for failing to follow proper procedures in clearing their shelters. Meanwhile we see bits and pieces of the lives of Fai’s friends: how Lou Ye is Vietnamese boat person left behind in Hong Kong when his family was accepted as refugees elsewhere; Chan Mui, a former night club hostess who is now a dish washer; Dai Shing who was once both an electrician and a Taoist priest but is now badly addicted to drugs and others. While getting food distributed by volunteer groups, Fai approaches a young man and invites him to be part of their group. As he seems to have some sort of speech impediment, Fai starts calling him by a nickname Muk.

Personally I found the main plot about suing the government for clearing their cardboard shacks not very interesting and Fai as the main character very irritating. He complains for example about all of the new apartment complexes coming up in Sham Shui Po which he thinks should remain as a neighborhood for poor people. He is also very stubborn, insisting that the government offer an apology and refusing to settle for a compensatory payment even though everyone else is in favor of it. What redeems the film in my eyes is that he seems to be the only one of his group who thinks this way. The others point out there are buyers for the new apartments and no one likes seeing a homeless encampment just outside their building, not even themselves if they could afford a unit. So while director Jun Li still comes across as being sympathetic to Fai’s views, it shows that he has considered both sides of the argument. It also suggests that Fai may not exactly be right but there is something admirable in his quixotic insistence on personal dignity and on having his own no matter what everyone else thinks and no matter the practical needs of his life. As he keeps saying, no one can save anyone else which I might rephrase to mean that you can only save those who want to be saved and Fai himself is certainly someone who doesn’t want to be saved.

While this film is meant to stir indignation at how poorly the homeless in Hong Kong are treated by the government, it had quite the opposite effect on me. For example it’s impressive that Chan Mui actually did manage to get public housing even if she had to wait a long time for it. None of the homeless seem to have to go hungry as they regularly get food from volunteer groups. Despite being frequently high on drugs or drunk in public, they are never arrested by the police for it. They even get away with minor shoplifting all the time. All things considered, they seem a lot better off than the homeless in other rich countries. One angle worth considering is that the film was made in 2019 when Hong Kong was experiencing unrest on an unprecedented scale. It’s possible that this might have forced the director to pull punches in his critique of the government. As it is, this film does help you understand a bit more about the plight of the homeless in Hong Kong but it’s not clear from this account how this is the fault of the government or even the system in general.

This means that in the end I found myself liking the film quite a bit but I’m sure not in the way that the director intended. There is a lot of room for differing interpretations because the background stories of the characters that we get are so sparse in detail. We never really learn why Muk ended up on the streets even though his family seems well-to-do for example. Mainly though the homeless in Hong Kong aren’t really homeless because homes are expensive, it’s because they have other serious problems in their life. Meanwhile homes there really are too expensive, but the results are that people are forced to live in their parents’ place for far too long or rent increasingly tiny subdivided spaces. It’s an entirely different issue from being homeless.