With its title, this sounds like it should be a truly terrifying horror film but it’s really a samurai drama. What’s more, it begins with plenty of action, a depiction of the real Heiji rebellion 1160, yet that only serves as a preamble to the real plot. In fact this is actually a story about a samurai who falls in love with a woman and becomes obsessed with her to an unhealthy extent. This is a surprisingly colorful and good looking film. I don’t care for how terribly the Lady Kesa is treated here, but I have to concede that it does portray the demands of honor of that period in an artistically pleasing manner.

The samurai Endō Morito remains loyal to the daimyō when the rebels seize the palace as part of the coup. A woman, the Lady Kesa, volunteers to impersonate the daimyō’s sister and he escorts her away as a distraction while the real daimyō’s family escapes. After the rebellion is put down, Lord Kiyomani rewards the samurai who have been loyal and asks Morito what he wants. He declares loudly that he has fallen in love with Kesa and wants her as his wife. A courtier informs them that Kesa is already married to Wataru, a samurai of the palace Imperial Guard. Morito is undeterred and insists that his lord owes him the match for his service. Kesa is alarmed when she hears about the scandal but Wataru takes it in stride and promises to protect her. When Kesa makes it clear to Morito that she doesn’t return his feelings, he only becomes more abrasive, breaking all the rules of decorum and honor, and challenges Wataru in a horse race.

The opening scenes of the film certainly look dramatic, showing the chaos of the coup attempt and the throngs of fleeing civilians. There’s also the drama of Morito discovering that his own brother is one of the leaders of the rebellion and helping Lord Kiyomani uncover and dispatch a spy. All this helps establish why Morito can get away with such outrageous behavior later but aren’t actually part of the main story. The film itself is really about Morito using his status, as a samurai and as a man, to force his attentions onto Kesa. Her husband seems to trust in their governing system and Lord Kiyomani’s honor, and so fails to understand how distressing it is for her. It’s like a very early film about toxic masculinity with all of the other men being so secure in their respective positions that they don’t see Morito’s actions as going overboard until it’s too late. Interestingly, Wataru behaves like the consummate gentleman, losing graciously to Morito in their competition and allowing Kesa to visit her aunt during the crisis. The director Teinosuke Kinugasa doesn’t seem to have any intention of assigning any blame to him. It’s all on Morito who let his passions overcome his sense of honor.

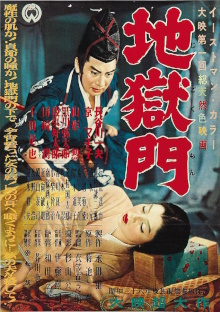

The film does look good and the colors in it are shockingly vivid, enough so that I wondered if it was colorized later. It seems that it really was made this way and is even known as the first Japanese film in color to be released outside Japan. You can see the color everywhere on the flags and heraldry of the different samurai forces, the barding on the horses, their tents and so on. The themes and the story are also interesting only inasmuch as it meaningfully depicts the traditional, now hopelessly outmoded, concepts of honor and the status of samurai. This is a film with a very narrow focus and a very specific moral sensibility. Film buffs will want to watch it as will those fascinated by the history of the samurai. Anyone else will probably want to skip it.