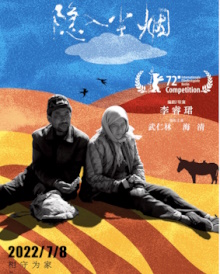

This was a low-budget art house film that did unexpectedly well at China’s box office and then seems to have been quietly censored. There was no official announcement but it was simply removed from cinemas and streaming services. On the face of it, there’s nothing in this very old-fashioned story of poor peasants in Gansu province that seems objectionable. Yet the abject poverty that it asserts continues to exist in the present day probably doesn’t accord with the Communist Party’s vision for China and its depiction of how government measures to alleviate poverty are instead often subverted for the benefit of the well-to-do probably doesn’t help. It’s too traditional and straightforward for me to really like but there’s something to be said about its plain simplicity.

Ma Youtie is a poor farmer who ekes out a meagre living working land owned by others. Being unmarried, his family arranges him to be married to Cao Guiying. Being disabled, infertile and incontinent, she is considered unmarriageable and her brother is eager to unburden himself of her. Youtie accepts her without much comment and with the help of his donkey, shows her the routines of life as a farmer. Over time, the couple develops a tender and companionable relationship. They live a simple, self-sufficient life, even building their own home out of mud bricks. Others take advantage of them but Youtie maintains a stoic and uncomplaining attitude. A powerful local businessman who rents the villagers’ land needs a blood transfusion and only Youtie has the matching blood type. He uncomplainingly complies without asking for anything for himself in return. Vacant houses in the village are demolished in order to qualify for a government cash incentive and he simply moves out of them when asked to. Despite the hardship they face, the couple appreciates the small moments of happiness they possess.

I’ve mentioned before that I dislike films that amount to being nothing more than misery porn and Return to Dust, to some extent, appears to qualify. It doesn’t quite fit however as Youtie never wastes effort on lamenting his own lot in life and does take delight in simple pleasures. It shows the work that he needs to do as part of his life in intricate detail: plowing, sowing and harvesting wheat, packing mud into bricks, thatching straw to make a roof, and much more. This makes the film feel very authentic and interesting even if there’s not much in the way of plot going on. The cinematography and acting are both great, with plenty of outstanding shots and characters that not prettied up. It’s worth noting that Youtie seems to be among the very poorest in the village by some distance so this portrayal isn’t at all typical of life for anyone else even where he lives. Those who take advantage of him aren’t unduly cruel either. They’re simply much more worldly and self-interested than he is.

The main draw to me is that the film is almost like a documentary in how deeply it goes into the rural lifestyle. It is utterly unromantic, not shying away from showing you just how much physical labor is involved in farming. Even watching the heavy loads their donkey has to pull had me cringing on behalf of the poor animal. I’m not a fan of the old-fashioned approach of portraying simple peasants as being inherently virtuous or noble. Yet it does make for a subtle and incisive critique of the Chinese ruling authorities, pointing out that despite all the modernization and prosperity of the past few decades, pockets of abject poverty. Worse is that the rich businessmen sound awfully like the feudalistic landlords of the past. I wish I had a better understanding of the financial relationships between the characters and how exactly the government’s cash incentive to demolish old buildings work, but it’s clear why it makes for a picture of China that is at odds with the vision that the Communist Party prefers to sell to the public. The film doesn’t explicitly show exactly what happens to Youtie in the end, but it’s easy enough to infer from the context and it’s not a happy one. As we’ve seen before, the authorities apparently tried to impose their own happy ending before taking down the whole film.

I was never going to be a big fan of a film as simple and straightforward as this: it’s full of stock characters with little psychological depth and China’s government is actually right that it doesn’t fairly represent the country as it is today. It is a beautiful film though and it’s admirable of director Li Ruijin to critique the authorities in this indirect manner so I’d recommend it anyway.