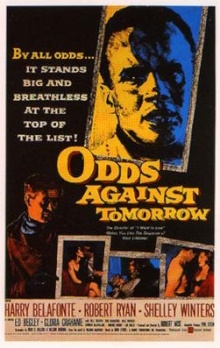

This is a film noir that is remarkable on multiple measures for something from the 1950s. The lead is a black man, played by superstar Harry Belafonte. It’s nominally a film about a bank robbery, but the robbery itself is the least important part. It’s instead an in-depth portrait of two very different men and why they were driven to commit this crime. Finally, even though it’s a noir, most of the scenes actually take place in the day time. It’s all the better for it too as we then get all these outdoor shots of the New York of the period. The anti-racism message is too on the nose for us now but the film as a whole is solid and well worth watching even today.

A former policeman David Burke decides to turn to crime after being fired and calls on two of his contacts who he knows to be desperate to join him in a bank robbery. One is Earle Slater, an aging military veteran and ex-con who is financially supported by his girlfriend. The other is Johnny Ingram who has a steady job as a nightclub singer but is in debt to a loan shark due to a gambling habit. Johnny refuses due to the high risk involved but relents after Burke leans on the loan shark to threaten his ex-wife and daughter. Earle is a racist who walks out after learning that he has to work together with a black man. He comes back after feeling inadequate as a man for being able to provide for himself. This doesn’t seem like the best team but Burke proceeds with the job anyway.

The robbery itself takes up only about the last fifteen minutes of the film and given the setup, there’s no surprise how it’s going to end. The real meat of the film are therefore the psychological profiles it offers of Earle and Johnny. It’s a surprisingly deep and complex take on the two very different men. Earle may be an irredeemable racist but that singular trait doesn’t fully define his character. He behaves like a grumpy old boy with other white folks and his background story of being forced to leave his family’s Oklahoma farm during the Great Depression isn’t wholly unsympathetic. Johnny genuinely loves his daughter and still has feelings for his ex-wife. He can’t stop himself from gambling however and is disdainful of his ex-wife’s attempts to integrate into a respectable middle-class life, calling it the world of the whites. Robbing a bank does sound like a desperate plan and this film seems to take seriously the question of what might drive a man to it.

The anti-racism message is obvious from the opening scene when Slater smilingly calls a little black girl a pickaninny. Meanwhile Johnny and his daughter have a perfectly normal and happy day at Central Park with all of the diversity of New York on display. At first it seems odd yet novel to see this in a noir. Yet the conflict between the two characters is worked into the outcome of their heist so clumsily and predictably that it drags down the film as a whole. The portrait of each of the two characters is quite good but the two simply don’t have any meaningful interactions with each other beyond mutual antagonism. Burke comes across as being stupid for thinking that these two can work together.

There’s still plenty to like about it, the black lead, how it deliberately veers away from the usual noir tropes, the strong acting and most of all, the outdoor scenes of New York. It’s also notable that there are so many idioms and other forms of colloquialism in the dialogue, making it difficult for my wife to understand. It feels a little strange even to me as they speak so indirectly about matters and I wonder how realistic this is. It does date the film more to a specific period, making it even more of a time capsule.