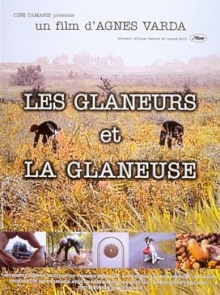

This is another one of Agnès Varda’s documentaries, or video essays really, that she made late in her life. It won me over right from the beginning with the title card of her production company Ciné-Tamaris being her cat in her own house. Since everyone likely is wondering what gleaners mean, she goes straight to explaining the word from the Dictionnaire Rousseau. The film follows Varda as she travels all over France with her handheld digital camcorder to meet the people who gather the leftover crops after the harvest from fields in the countryside or scavenge food and trash in the cities. As the French title makes clear, Varda considers herself a gleaner as well as she gathers ideas, inspiration and meaning from those she meets.

The definition of the word ‘glaneur’ in French as given in the dictionary conveniently includes as illustration in the form of the oil painting by Jean-François Millet completed in 1857. Varda uses it as both inspiration and starting point to track and follow gleaners in the modern era. She begins with foragers to collect potatoes that are thrown out due to being of an unsuitable size and shape to be sold in supermarkets. She befriends them and asks questions about why they forage and how they came to live lives on the periphery of society. Some wander to forage as they please and others do so with the permission of the landowner, following a fixed distance behind their harvesting operation. In the cities, she meets artisans who collect trash to turn into works of art but also those who scavenge food from rubbish bins and from the leftovers on market days. She discusses the lawfulness of such gleaning with legal experts and the ethics of wasting food and useful objects, all with a non-judgmental eye. Along the way, she reflects on her own advanced age and mortality, commenting frankly that the end is near for her.

This doesn’t feel much like a documentary as Varda puts so much of herself into it. Her sense of presence is palpable in the way that her interlocutors respond warmly to her and I guess that she has so much access at least partly because of who she is. It’s always a delight to vicariously feel her joy in coming across interesting people and objects across France. Not all of her digressions are quite on topic. For example she meets with a descendant of Étienne-Jules Marey, a pioneer of photography, to examine the chronographic gun that he used to capture animals in movement. Nor are all the people she meets poor and deprived. One of them is Jean Laplanche, a famous psychoanalyst who also happens to be winemaker. Her own whimsical thoughts on catching lorries on the highways, experimenting with the freedom afforded by the light camcorder and musing about her own wrinkled and gnarly hands are similarly off topic but they are all fascinating to ponder.

I really appreciate her soft touch and gentleness in talking with the interview subjects. Many of the gleaners who forage food out of real need obviously have complex stories to tell. Some have lost formal employment due to problems with drug and alcohol addiction. She chooses not to dwell on the negative aspects and instead focuses on the positives that they get from gleaning. When she meets a Michelin-starred chef, she gently teases him as he obviously can afford to buy his own food. He replies that his grandfather taught him the habit and that as chef, he likes to know exactly where his ingredients came from. Then there’s the activist who scavenges for food from garbage bins in the city as a form of protest against capitalist greed and overconsumption. She treats all of them as equals and lets the narrative lead her wherever it will. Sometimes when the things don’t seem quite legal, such as those who forage for oysters blown by storms from the beds owned by, she lets their conflicting statements contrast each other.

I didn’t think that I would like this so much but I did. It combines a sense of romanticism for rural France and a bygone era with modern questions of logistics, food security and poverty. It dips as it wills into history, culture and tradition and Varda eagerly absorbs it all to make use of what little time she has left. In this way, it invites the viewer to explore and consider the parts of France that aren’t so visible in the public consciousness and of course Varda subtly signals that the migrants too are part of France.