Experimental films are usually difficult to make sense of but that is very much not the case here. The putative director William Greaves explicitly explains what he is doing and his crew further contribute their own theories. The real question is whether or not the end result is anything interesting or worthwhile. That’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer and it’s not even obvious if Greave is really as inept a director as he appears to be here. It appears from his filmography that he actually is a competent filmmaker so the apparent chaos here must be deliberate and so this is a work of art after all.

A male and a female actress play a husband and wife confronting each other in New York City’s Central Park. The wife accuses the husband of being a closet homosexual who doesn’t want to have children with her. The husband denies her claims and asserts that she is being crazy and irrational. The same scene plays out again and again, sometimes with different actors. But we are also shown the process of filming itself. Greaves has three sets of crew working, one to film the actors, one to film the first crew and a third to film everything else including random spectators and passers-by. As such we also get to see the myriad technical struggles with the equipment, kids crowding around to see what is going on and even a policeman coming by on a horse to check if they have a filming permit. After days of filming the same scene, the crew gather by themselves to debate what is going on. They agree that the project doesn’t make sense and the script, written by Greaves himself, is banal. Some argue however that meaning arises from its very banality. Others assert that the crew should take the freedom that Greaves has given them to make something new and unique on their own.

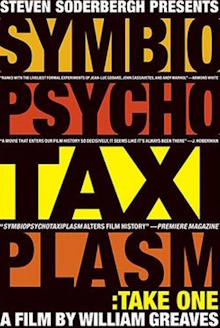

Nothing in here is particularly novel nor exciting nor even dramatic. What it does have is brutal honesty as Greaves seems to break down the reticence of everyone to be just themselves and forget about the omnipresent cameras. The actors graduate from discussing the angle and speed of their walking through the scene to badmouthing each other. The crew freely offer ever more sophisticated theories of what Greaves is really trying to achieve and whether or not the film constitutes art. One of the primary proponents for this film is Steven Soderberg who rescued it from obscurity. As he notes, it’s similar to a reality show but since this takes place before reality TV, most of the people in it are less self-conscious about being themselves part of the spectacle. Greaves himself is certainly aware of what he is doing and so plays a character instead of being himself. He evinces a subtly sexist attitude, gives vague directions that suggest that he is uncertain about what he wants and seems to have generally poor taste about what is good. This is certainly meant to encourage the actors and the crew to mutiny against him.

To me, that’s enough to qualify it as being an interesting art experiment. It’s fascinating to watch the crew members, all seemingly intellectual types with a solid education in the arts and philosophy, react to the paucity of the material Greaves offers. So they overthink and play off of the ideas of each other in search of an interpretation. Similarly the actors themselves are far more sophisticated and self-conscious than the characters they play. The male lead for example expresses frustration at not knowing exactly what type of homosexual his character is supposed to be, a quietly closet one or an overly masculine one. Meanwhile Greaves gives every impression that the actor has given far more thought to it than he has. Towards the end, a homeless person who sleeps in the park approaches them. Greaves decides to keep the extended oddball conversation and even has him sign the release form for appearing in the film on-camera. The crewmembers seem sympathetic at first but then slowly try to back out as the man sounds increasingly unhinged.

Still the concept of the film is cooler than the execution. This is fun to watch as it’s so short but it’s not like it surfaces anything that is truly novel. Plus as Soderberg observes, this is somewhat like reality TV and today we’re inundated by this type of content. Greaves eventually made a sequel to this twenty five years later but I don’t think I’m interested enough to watch it.