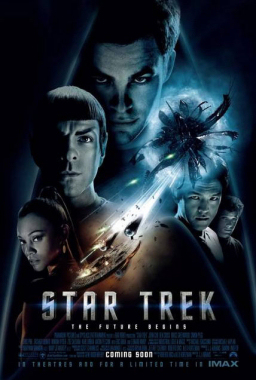

Inevitably, I went to see the newest Star Trek film with my wife on Sunday. Now, I’ve always thought of myself as a Star Trek fan, even though I’m too young for The Original Series and it’s The Next Generation that is the most memorable for me. I never did get around to watching Deep Space Nine, only watched bits and pieces of Voyager and made a deliberate effort to avoid watching Enterprise.

Still, I’m reasonably up to snuff on the best parts of TOS and combined with the best parts of TNG, I have a very firm idea of what it is that makes Star Trek great: as a mainstream platform on which to tell high-brow science-fiction. After all, it’s not a coincidence that many of the very best episodes were written by the most notable writers of print-based science-fiction, for example, City on the Edge of Forever (TOS) by Harlan Ellison, The Measure of a Man (TNG) by Melinda Snodgrass, The Doomsday Machine (TOS) by Norman Spinrad etc. Plus, there’s the fact that Star Trek always had a single very clear vision: creator Gene Roddenberry’s dream of a unified and noble humanity venturing out to do good amongst the stars.

Continue reading Star Trek is dead. Long live the new Star Trek