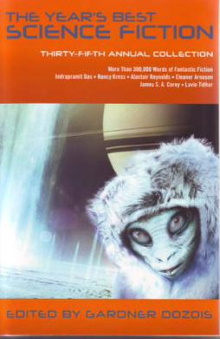

I haven’t been so diligent as to buy anything close to every edition of this annual anthology of the year’s best science-fiction stories but this has indeed been a semi-regular fixture of my life ever since I started reading fiction from way back during my school days. This particular edition however is the very last one as editor Gardner Dozois died in 2018. This truly marks the passing of an era for although he is not well known for his own writing, his editing work has been influential in the field for decades and as this volume illustrates, he does invaluable work in documenting what happens in the field of science-fiction every year.

Unfortunately, last volume or not, this is not a particularly strong collection of stories, as other reviewers have also noted. Out of all of the stories here, I’ve only one of them before, Greg Egan’s Uncanny Valley, about a synthetic being programmed with the memories of his progenitor, and as usual I’d rate this as one of the best in the book. Other stories that I would consider as excellent science-fiction include We Who Live in the Heart by Kelly Robson about a group of pioneers who rather than live safely underground on an alien planet choose instead to make homes out of giant, whale-like organisms; The Wordless by Indrapramit Das about a population of engineered humans made to serve as workers to service starships on an insignificant world in-between more destinations; and to a lesser extent Whending My Way Home by Bill Johnson about a time traveler stranded in the past and who has to go home by living a day at a time while ensuring his timeline is preserved. They are all solid stories but I don’t think any of them are revolutionary.

Some others are okay I suppose but too many feel derivative. I liked the Hindu aesthetics of The Moon is Not a Battlefield also by Indrapramit Das but it is at its heart the old story of a super-soldier abandoned by her masters after the end of the war and ill-adapted to life on Earth. Mines by Eleanor Arnason about a colony and the soldiers on it losing contact with Earth during a war and having to deal with depression is somewhat similar. Several more are about encountering strange people who are incongruous to the present time and place. These include Michael Swanwick’s Starlight Express, Maureen F. McHugh’s Sidewalks and maybe Sean McMullen’s The Influence Machine. They’re not bad but it’s well-trodden territory and ironically their very presence in a volume of science-fiction takes away some of their mystique. The reader knows what is really going on long before the point of view character does so the character’s reluctance to believe in something incredible feels grating.

One growing category of stories that I welcome however are those that confront climate change. Those certainly feel timely and The Proving Ground by Alec Nevala-Lee is a nice long read that is about both the technical and the political difficulties of rising sea levels. But it’s also a cautionary tale about the unpredicted perils of geoengineering to address the problem, which I tend to dislike. Somewhat similar is The Last Boat-Builder in Ballyvoloon by Finbarr O’Reilly in which a bioengineered solution for the plastic pollution in the oceans turns into a Lovecraftian nightmare. At the other end of the spectrum, we have Pan-Humanism: Hope and Pragmatics by Jessica Barber and Sara Saab. As this is about a pair of friends and occasional lovers who grew up in Beirut to become noted scientists involved in improving the environment, it occurs to me that this story makes for the perfect poster child of the highly mobile technocratic elite who are so derided by the Trump crowd. I am all for this vision of future utopia of course, but it does stand out how the main characters and all of their friends are all hyper-competent, super-specialized knowledge workers who fly all over the world to work on all kinds of projects and rarely stay in any one place for long.

Finally there are the stories that are just plain fun. Nexus by Michael F. Flynn is the kind of story I wish I had written myself, about a bunch of science-fiction character archetypes including aliens, time travelers, an android, a mutant and so run into one another due to a freakish coincidence, all of whom were not previously aware that the others existed. As for Bruce Sterling’s Elephant on Table, I could never have written that but it’s such a sly take, extrapolating on current social and political trends. Some other stories I liked but they feel like the first chapter or so of a novel. This particularly makes sense for Alastair Reynolds’ Night Passage set in his usual Revelation Space universe. But I also felt that Triceratops by Ian McHugh about humanity reviving both Neanderthals and creating hybrids of them with Homo sapiens seems incomplete.

Overall I still feel that this is a weak volume and I would hesitantly offer a few possible reasons for that. One is that society is now changing faster than the imaginations of science-fiction writers can keep up with. This has never been more evident than this year as the pandemic is accelerating changes in how we live and work beyond anything anyone could have imagined. That’s why several stories set in the near-future in this book feel positively dated not only in their assumptions of what life looks like a few years from now but also in the language that they used to describe society. Our lexicon now contains so many new words that comes to us so naturally that stories that fail to keep up feel antiquated. It’s so odd when a writer uses the word ‘unicorn’ to refer to the mythological animal instead of a company. One exception here is A Series of Steaks by Vina Jie-Min Prasad about printing meat and features a thug hired through a gig app but I fear that even this seems doomed to obsolescence in a few more years when we get real 3D printed meat.

Another reason is that I fear that there isn’t enough money in science-fiction stories to attract the best, the most brilliant thinkers. The amount of money currently available to fund television shows is now truly astronomical and there are so many genre and genre-adjacent shows that full of creative ideas. Stories published in a magazine with low circulation just can’t compete. Then as this volume also states, plenty of well-funded companies also hire science-fiction writers to imagine near future scenarios and dream up ideas. Some of these eventually make it to the general public but I’d bet many more don’t. After all, why work on possible near-future products and services just to have them appear in fictional stories when investors would be happy to throw money at you make them real? In short, I feel that science-fiction is in a weak place currently because the future is happening right in front of our eyes.

One thought on “The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Thirty-Fifth Annual Collection”