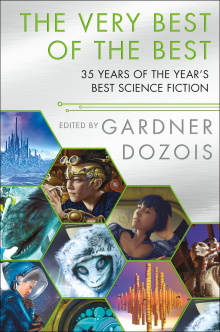

After reading the last one of the late Gardner Dozois’ science-fiction short story anthologies, it’s time to move on to this best of the best series as I’d missed many of the annual ones and I’m not likely to go back for them. The subtitle is a misnomer however as this is apparently the third volume of the series and hence it covers only the years 2003 to 2017 and not actually the full 35 years of his career. It’s been so long that I can’t remember if I actually already own the first volume published in 2005 but I do recognize most of the short stories. I definitely haven’t read the second volume published in 2007 so I suppose that’s one book to look forward to.

As to this book in particular, I’m pretty sure that it’s the biggest single volume anthology of stories I’ve ever read. Getting through this doorstopper was a time-consuming affair even for me. As in any anthology, there are stories that I think are great and some that I think are duds, but the overall quality truly is outstanding, not a big surprise given that Dozois was able to pick from about 15 years of the best stories he’d seen. I’d only read three of these before so almost all were new to me. This book even includes a story by Greg Egan, still my favorite science-fiction writer. Unfortunately while that story, Glory, set in his familiar Amalgam-universe starts strong with a highly technical yet plausible technique for persons to be transmitted as information at light speeds, it was a disappointment to me. It directly addresses one of the more critical questions I’d always had about Egan’s vision for the future: how do enlightened, pacifist civilizations deal with hostile, belligerent ones and Egan seems to have no original answer to that except the old-fashioned Star Trek Prime Directive one of avoiding contact.

Some of my favorite stories in this volume are familiar or even mundane ones transposed onto a novel setting. An excellent example is Ken Liu’s story whose very long title I will shorten to just The Long Haul. It presents an alternative history in which the Hidenburg disaster never happened and so airships are a viable vehicle for bulk freight as well as leisure. This is a low -key story but I loved the details of this alternative world, the American-Chinese inter-cultural exchange and of course as we are currently looking for ways to deal with global warming, airships truly would be a viable alternative to jet engine-powered aircraft. Similarly Eleanor Arnason’s The Potter of Bones recounts the familiar process of one lonely person discovering the theory of evolution, but from the perspective of an, to us, alien species on an alien planet. It’s part of the author’s Hwarhath setting which I’m not familiar with but what rich and compelling worldbuilding. This may be my single favorite story of the book.

Another story that stood out to me on the strength of its worldbuilding is Robert Reed’s Good Mountain. This is again one of the author’s established settings that I’d not previously read but this story serves as an excellent introduction to this world that is so ordinary and at the same time so weird. The story is about a man’s journey to flee an impending catastrophe, and that immediately brings to mind our current climate crisis, plus his method of transport is riding inside a giant worm. Now doesn’t that remind you of something? I also liked David Moles’ Finisterra about animals so gigantic that they serve as floating islands and Weep for Day by Indrapramit Das about a world permanently divided into day and night and the civilization which lives in the twilight invades the dark. On the other hand, Aliette de Bodard’s Three Cups of Brief, by Starlight didn’t impress at all. Once again, I’ve never read anything from her Xuya setting before this and while the Vietnamese inspiration is intriguing, I don’t see the appeal honestly.

In general, I found that the space opera, action-adventure, and young adult stories here tend to be my least favorite ones. These include John Kessel’s Events Preceding the Helvetican Renaissance, Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette’s Boojum, Paul McAuley’s Dead Man Walking and Rich Larson’s Jonas and the Fox. It’s getting harder and harder to write plausible, technologically sophisticated action-adventure that isn’t just a kind of cartoon violence. I did love The Illustrated Biography of Lord Grimm by Daryl Gregory which is in a deliberately cartoonish and yet horrifying send-up of the superhero genre featuring a country that is recognizably Dr. Doom’s Latveria. I do wonder why there aren’t more science-fiction writers that try writing serious superhero stories, John C. McCrae’s Worm certainly shows that it is possible.

One story that I felt was just first rate science-fiction is Rates of Change by James S.A. Corey, about a future in which people can wear new bodies by moving their brains and nervous system but one woman develops a pathology whereby she feels that her new body is not her at all. The Little Goddess by Ian McDonald deserves special mention for the excellent portrayal of a near future India. Another brilliant story is The Things by Peter Watts which retells the well-known story of The Thing from the perspective of the alien. I love the concept but it relies very heavily on the reader possessing very detailed knowledge of the original story and as much as I enjoyed it, I can’t recall what every character did in it. Somewhat similar is KIT: Some Assembly Required by Kathe Koja and Carter Scholz about the playwright Christopher Marlowe being brought back as an AI. I’m sure it’s very good if only I actually know something about his plays as it’s chock full of references.

Anyway that represents a fair number of stories in this book already and I have no intention of covering everything. I will note that after spending more time and effort watching interesting films, I now perceive that some of the psychological characterization in science-fiction stories are so simplistic. One example here would be Calved by Sam J. Miller about the generational gap between a father and his son. On the face of it, it ought to be decent but I could see the twist coming from so far away that it made no impact at all by the time it arrived. Science-fiction is of course a genre where the setting is often more important than the characters but I do sometimes wish for richer characterization and more complex psychologies. Then there are stories like Useless Things by Maureen McHugh which I really wanted to like, but it just kind of peters out and leaves so many things unanswered.

Overall this is undoubtedly a great anthology of science-fiction stories and well worth the time and money. I think I will pick up the second, earlier volume sometime down the road so this will not be the last Dozois published work I will read. But it does make me feel even more keenly how his contribution to the field will be missed. Sure there are other editors compiling annual anthologies but I don’t think anyone can match his stature and broad grasp of the field.

One thought on “The Very Best of the Best: 35 Years of the Year’s Best Science Fiction”