These are gods who have been forgotten, and now might as well be dead. They can be found only in dry histories. They are gone, all gone, but their names and their images remain with us.

…

These are the gods who have passed out of memory. Even their names are lost. The people who worshiped them are as forgotten as their gods. Their totems are long since broken and cast down. Their last priests died without passing on their secrets.

Gods die. And when they truly die they are unmourned and unremembered. Ideas are more difficult to kill than people, but they can be killed, in the end.

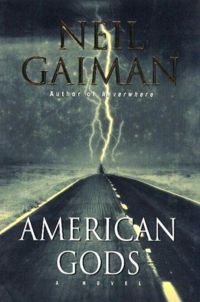

– Neil Gaiman in American Gods.

Quite a few comic book writers have over the years tried their hand at writing novels, but none have achieved as much mainstream success and recognition as Neil Gaiman, winning the Hugo, Nebula and Bram Stoker Awards for Best Novel for American Gods. This is partly explained by the fact that Gaiman actually co-wrote a novel, Good Omens, together with Terry Pratchett, before ever venturing into comics, which he did in a big way, by taking up the mantle for Miracleman following Alan Moore’s departure from the series. Nevertheless, Gaiman is best known for writing the highly acclaimed Sandman series from 1989 to 1996.

American Gods features some of the same themes as The Sandman and deals with the subject of gods, in this case, once great gods whose powers have waned as their worshipers have died off and their religions fallen into obscurity. Set in contemporary times, the novel follows the adventures of Shadow, a recently released convict from prison, as he travels across the United States while working for a mysterious employer, meets with a large number of decidedly odd individuals and learns quite a few secrets along the way, including secrets about himself and the nature of America.